Mary Akers: Hi, Ron. Thank you so much for agreeing to talk with me today. I loved your short story BOOM! for so many reasons, especially the point of view, which is that of a Marshallese young man with big dreams and hopes for how (he believes) love intersects with those dreams. I was a big fan of Jeton in both this story and in your wonderful novel MISSILE PARADISE which it was my great pleasure to read. Jeton plays a big role in the novel and gets into trouble a lot, but you do such a fine job of taking us through his thought processes that we really root for him to succeed. Would you like to say anything about your relationship (as creator) to Jeton?

Ron Tanner: Thank you, Mary. I have great affection and sympathy for Jeton. As I have worked with Marshallese teenagers, I knew something about the world he inhabits. To make him a viable character, he had to have agency—an agenda, a dream, a stubborn streak to follow. He couldn’t simply be a victim. To curry the reader’s sympathy, Jeton had to make mistakes as he followed his agenda. I knew he’d get into trouble but I wasn’t sure how bad it would get for him.

MA: I also loved your rotating points of view. I’m a big fan of that style of writing I guess because I feel like all of my life I’ve been aware of the fact that each story has many versions. Or, perhaps better said, each principal character in a story has his own convoluted take on that story. Cooper is a great character. I feel like I’ve seen people like him so many times in my life–the expat who leaves his country looking for excitement and challenges and runs smack into a brick wall–or a wall of water. There’s a really wonderful passage on page 265 that I keep returning to because it speaks so well to the American dream as it collides with the American experience.

“Cooper thinks of peasant factory workers in China punching out golf balls, five thousand a day. What is that work compared to his own? Is his work–despite its many acronyms–any more useful? He suspects that it is not. In fact, it may be less than useful, like selling parachutes to people in high rise buildings in the expectation of another 9/11. Do you really think that, when and if they hit your building, you’re going to have time to dig out your chute, strap it on, brace yourself at the window (assuming your window opens) and then bail yourself into the city traffic fifty stories below?

“There will always be crazies, there will always be bombs. Everybody knows that much. What nobody knows is how to live with this uncertainty. The work at USAKA must make some people feel more certain, especially at the Pentagon, he imagines. Never mind that the fruits of this labor have been decades in coming. In the meantime, year after year, the engineers, technicians, and programmers like himself burn billions of America’s dollars on their computer screens and in their finely drawn schemata. In many ways, it’s no more or less than alchemy, Cooper decides, everybody looking for the formula to make gold.”

That passage is so great. Tell me something about how you came to understand and write Cooper’s point of view.

RT: Thanks. Cooper is young enough to be a big-time dreamer—the world hasn’t beaten him down (yet). But he’s beginning to see that all isn’t as free and easy as it once seemed. Specifically, the American presumption of superiority unsettles him. Now, he finds himself doing work that, despite the hype, seems to be useless. It’s making his head spin. This is what happens to many, if not most of us, as we mature. Or so it seems to me: Growing older is mostly about managing disappointment. Cooper is just beginning that journey in earnest.

MA: I really love Art, too. His cranky take on Americans especially speaks to me. He tells Cooper,

“Americans are just bauble-dazed peasants. They’re doing what anybody would do after stumbling into Ali Baba’s cave. Forty years ago, before I left for the Corps, the most popular show in the States was ‘The Beverly Hillbillies.’ That’s us. We’re eating supper around the pool table thinking it’s a fancy dining room. And we’re hemorrhaging money to live like that. It’s tragically hilarious.”

Tell me something about who Art is to you.

RT: Art is based on a Peace Corps washout I met in the 1990s when I visited Kwajalein. He still had hopes, still wanted to fight the good fight but knew, too, that his day was pretty much done. He’s the conscience of the novel and my favorite character.

![Missile Paradise by [Tanner, Ron]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51e4R9ml5tL.jpg)

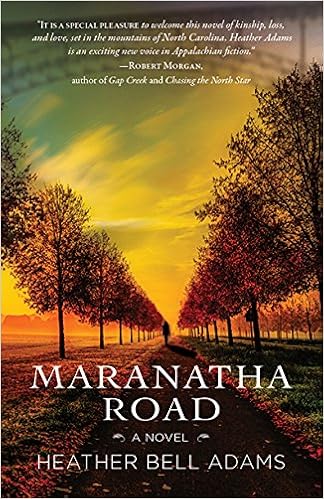

MA: I love the cover of your book–could you describe the process of designing it?

RT: My publisher came up with two designs. This one hit the mark dead-on. I had nothing to do with it but was grateful that had found a talented designer. The cover conveys a jaunty, almost comic spirit, which suits the book.

MA: It definitely does! Can we talk a little bit about self-publishing? I’m really fascinated by the process and I’ve been considering going that route, after two consecutive novels failed to ignite the minds of any editors. What are some of your favorite and least favorite aspects of taking control of the end product in this way?

RT: The great thing about self-publishing is that it gives voice to writers who have been silenced or shut out of mainstream publishing. The bad thing about self-publishiing is that it encourages everyone to publish when many of these writers aren’t ready to publish. I worked recently with a college sophomore who proudly told me he had self-published three novels. I advised him to proceed with caution—to slow down and give his writing more time to test itself.

In this student’s case, rushing to publication very likely undermined the advantages that drafting and editing would yield over time. For example, ten years from now, he may discover that he didn’t quite get that first novel right: it was a great idea but poorly executed. But he can’t re-publish the same book. Worse, no publisher in the business will be interested in anything that has already been in print (there have been a few, rare exceptions).

The first version of Missile Paradise—over ten years ago—got me a big New York agent who was convinced the book would sell big. She shopped it to the major houses but no publisher would take it because none of them knew how to market it—the novel didn’t fit the categories they thought would sell. So the agent dropped the book and me too. I was devastated. After re-drafting the book for years, I considered self-publishing it because I was convinced Missile Paradise was a good book. (By the way, the American Library Association named it one of the “notable” books of 2016.) Fortunately, I found a small-press publisher that was enthusiastic about the book.

I say “fortunately” because self-publishing is not easy. Not only is it expensive (though you can save upfront costs by doing print-on-demand), but it can also be exhausting: it’s hard enough to promote a book published by a small press. It’s ten times harder to promote a book all on your own. Studies have shown that self-publishing works best when the writer already has a following he/she can draw on. Self-publishing from a cold start—with no readership behind you—can be most daunting.

MA: Agreed. Can you tell me a little bit about how your interests in the Marshall Islands came about? And about the organization you founded to help tell the stories of the Marshallese?

RT: As a teenager, I lived on Kwajalein, the missile base I write about in Missile Paradise. It changed my life: Living among the Marshallese made me aware of the wider world, the privilege of Americans, and the profound differences rooted in social and cultural diversity. At bottom, my time in the Marshall Islands made me politically aware. When I returned to the states, I got politically active and motivated to bring about social change.

I returned to the Marshall Islands in 1993 to teach. Then, in 2008, I applied for and won a grant from the National Park Service to pilot an educational program that would teach Marshallese college students how to write better English and learn other real-world skills by 1) doing field work to collect tales from their elders (to preserve their oral culture), 2) translates these tales into English, and 3) make a website to broadcast these tales to the world. The program was a great success and can be found at www.mistories.org

MA: I feel like we have a somewhat similar approach to writing and life. I’ve traveled, lived in many places, been a potter, a military wife, a writer, co-founder of a marine ecology school, co-author of a book, I like to build and renovate, I like to re-envision spaces, I like to learn new things. I feel like you have a lot of parallel sorts experiences and interests in your life–making things and learning and taking on challenges. It definitely keeps life interesting, but sometimes I wonder if this breadth of experience has made the depth of my work suffer. Do you ever feel this way? If so, is it a source of comfort or discomfort? (Maybe like me it depends on the day.) If/when you feel this way, what do you tell yourself to make it feel right?

RT: Let me congratulate you on the breadth of your interests: you are living large. That said, I do admire those people who have singular passions that take them deeply into their one interest. But that’s not who I am (or who you are either, apparently). In order to be true to myself, I pursue many interests—that’s what makes me happy. But it has its costs.I am often stretched too thinly. Had I not done so many things, I might have written more books, for example. Currently, I am restoring an historic farm: it takes up almost all of my free time. Should I be writing instead? Yes and no. I am the writer I am, for better or worse, due to my varied interests. Much of my writing occurs when I’m not writing.

Which brings me to this: one of the big myths of writing is that you’re supposed to do it every day . . . and all the time. Not true. We are often writing—working through the problems of a story or an idea—when we’re not in front of the screen (or pad of paper). Obviously, you have to have discipline to write: that is, at some point, you have to sit down and make it happen. But that doesn’t mean you should feel guilty if the act of writing does not dominate your days.

MA: I like that answer. And finally, because we are a recovery themed journal, what does “recovery” mean to you?

RT: I think most of us are familiar with the process of recovery. In great part, it’s about getting back the best of yourself. Each of us strays at one time or another, in one way or another. The hallmark of maturity is that we realize this—and it humbles us. Which is to say: I don’t presume half the things I presumed when I was younger. That’s a good thing.

![Missile Paradise by [Tanner, Ron]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51e4R9ml5tL.jpg)