Mary Akers: Hi, Sasha. Thanks so much for agreeing to talk with me today. I just loved your poem “Fecundity, Expanse” in the July issue of r.kv.r.y.. When I first read that poem, I didn’t have a sense of how it fit into this whole wonderful themed collection of yours. Now that I’ve been reading your collection “Failure and I Bury the Body” I have an even better (perhaps wider) appreciation for the poem and its place amid a larger work of art. Something like seeing a beautiful detail of a painting and then stepping back and seeing a whole beautiful mural and going, “Whoa!”

I’m curious how this linked collection evolved. Did you set out to write a whole collection that was linked? Did you examine a grouping of poems and look for the links and then accentuate them? Did you map out the poems you wanted to write beforehand? Granting that the process for every collection is unique, how did it work for this one?

Sasha West: Thanks for including that poem in r.kv.r.y, Mary. In terms of the collection, I’d written one earlier allegorical poem in which a woman gives birth to a baby who is Loneliness, and I was intrigued with the idea of working with more allegorical characters. I’d been thinking about medieval allegories and how vices and virtues became flesh characters in them—and so I started thinking what our modern- day seven vices might be. After loneliness, failure came to mind, so I began drafting with the two main characters in mind—Failure and the unnamed narrator—and the project started to grow. The idea that the narrator was taking a road trip with Failure across the American Southwest came early. I knew I wanted them to be living inside of how climate change and nuclear tests and other bits of history have affected that landscape—and I knew it would be a long poem, but back when I started, a long poem to me was 6-8 pages. (The book clocks in at 128 pages!) Sometimes the project feels to me like a set of poems that come together into a whole and sometimes it feels like one poem that happens in parts. In one version of the manuscript, the pieces weren’t individually titled—so each new poem was a new section of road, a part of the single whole gesture through time.

The experience as it expanded was what I imagine writing a novel to be. As I was working on their story, I started discovering things about these characters and their world. I realized Failure was always performing strange little experiments as they went along, and so those came in, and then I realized the narrator was so ready to follow Failure because she felt broken and broken-hearted in equal measure. She was trying to leave something behind that wouldn’t stay left. Thus arrived the character of the Corpse who they pick up on the side of the road, who won’t stay buried—and the poem kept growing.

MA: I love linkages in both poems and short stories. I feel like they force us to do a little extra work (as readers) beyond what we are already doing when reading. And I say “work,” but I don’t mean that in an onerous or pejorative sense. I mean it more like the “work” that comes with discovery. It’s exciting, rewarding work, not laboursome. Does that make sense?

SW: Absolutely—and I agree. There’s a readerly pleasure in peeling back layers, in noticing patterns across a whole, in returning to the same landscapes or dilemmas at multiple points in a text and watching how they change. I feel like they engage our curiosity. And because linked poems or short stories have gaps built into how they give you information (more gaps, let’s say, than your average realist novel), they make the negative space around them active. I hope for that in this book: that a reader might notice Failure’s experiments and dream up others, that a reader might fill in the story of the Corpse that the narrator half- tells, half-obscures.

MA: Yes! Negative space! I think about negative space so much. I once had an undergraduate professor who made us draw an entire photograph (of ourselves, from childhood) and when we were “finished,” he made us go back and erase portions of it. It was a mind-expanding exercise for me that continues to inform my writing to this day. What is necessary? What is more beautiful in its absence? I feel like that is the essence of poetry–the condensation and distillation, the annealing of words.

Do you, as a reader, enjoy reading linked work?

SW: Yes! In fact I just had the pleasure of slowly discovering the links in your new collection Bones of an Inland Sea. I like it when those links feel organic and when they slowly unfold, as they do across your book. It feels like recognizing someone who is dear to you in the airport of a faraway city. I tend to read poetry and novels more than stories, so I especially love links in a story collection because I get a better sense of the map in the writer’s head—how all the pieces come together into a territory. I’m fond of linked poems for the way they can create that same expanse. While I don’t tend to write poems with traditional rhyme across lines, I am interested in the idea of rhyme across a book—the way repetition and variation operate to forge relationships between the various pieces.

MA: Thank you! I enjoyed finding and creating the links in that collection.

Your addendum FAILURE’S ACCOUNTING OF INFLUENCES is so fascinating and exciting. When I discovered it, it made me go back and reread the poems I had already read and look at them as part of a larger conversation, as art informing art. Was that your intent?

SW: Yes, it was. I knew I wanted to use some small elements of collage (or bricolage) and allusion in the work, but I didn’t want those elements to overpower the pieces and make the collection about the surface instead of the story. I feel like sometimes the thing in a poem that comes from somewhere else doesn’t become wholly embedded because we are so quick to call it out, to mark it as other. (Sometimes I feel like the notes sections are intellectual gossip—who is inside the poems, who has this person read, have I read the same people? Seen the same things?) All of that can distract from the work. I’m interested in visual artists who make something new of collage (Robert Rauschenberg, let’s say), and what we see is the whole rather than the sources, though the sources are also visible, embedded if you look closely enough. Obviously, there’s not really a way to do that in a book, but I was trying.

There’s also a way I want these characters to move through a world haunted by other things—paintings, news, books, maps, magazine articles. There’s a poem where the narrator tells a story about a trip she didn’t take to Antarctica and most of it is a recounting of Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World. It’s not her story, but she’s taken the film, swallowed it as a mythical place, and added to it. We do that in our lives with stories and objects and other people. We use what we find outside ourselves to explain life to ourselves. So I wanted all the allusions and echoes to be part and parcel of the project.

That might seem to argue for not marking these other bits of text at all—but there’s this other side of using someone else’s work where I am grateful to what I have they have given me. I also realize collage can be obscured in writing more easily than the visual arts. I needed a system of pointing, as Gertrude Stein might say. I wanted a way to point to the worlds inside the poems without marking them as something other or separate. The accounting came out of that. Failure’s character is experimenting and tallying and list- making, so he got to do that often in the book—and he was put in charge of the titles and the references.

MA: “A system of pointing.” Brilliant. The “Failure’s Accounting of Influences” pages also made me think about continuity. And not just continuity in art, but continuity in failure. And how close Failure rides beside us as we create. How this imaginary personification shadows us and haunts us but also cradles us and soothes us. So interesting. Would you like to comment on that?

SW: Years ago I became obsessed with the idea that we’re always looking at success when we’re learning to write—and that we are missing something because of that. Graduate programs teach the greats, and writers hand off beloved texts Xeroxed or copied from lit journals like so much samizdat, but we ignore everything that fails (or we relegate it to the territory of snark). I was teaching a class where we read through every book in order of some mid- to late-career poets—people I really admired who’d published between 3-7 books. When you’ve written that much, some of it is inevitably better than other work—and some of the books really failed. I was struck by how interesting the failures were—and how they often opened up space for some breakthrough (or just break) later. I wrote an essay called “In Praise of Failure” and tried to look at what it could do. I started seeing failure as a generous and necessary force in becoming an artist.

On the personal side, my twenties were marked by a lot of failures, things that didn’t go the way I’d hoped or intended. I wanted a more generative and hopeful way to think about the time. And I was casting about for a way to come to terms with our country’s failure to address climate change adequately. Our country has been terrible in so many ways and ghosts of that come into the book—blankets with smallpox, bodies dragged by trucks. Everywhere—as artist, person, citizen—I kept feeling this need to find something beautiful and strange in what was breaking. There’s a bravery in coming to terms with failure that I wanted my narrator to find. Perhaps I was hoping that would leak back from the book into my life.

And with all of these ideas circling around the manuscript, at some point Failure started being a character I felt a fondness for. I was interested in his childhood and his strange relationship to a pack of dogs that kept chasing him down trying to kill him. (No dice, as he is, of course, immortal.) I was interested in his vulnerabilities and failures—and his imagination. He felt like a strange god who’d settled into our house in a benign way, something I should treat with tenderness—something with fur and a pulse.

MA: “In Praise of Failure.” I would love to read that essay. It should be required reading, actually.

My two favorite poems in Failure and I Bury the Body (so far) are “Machine That Leaves and Never Returns” and “Failure Dreams of Elements.” I imagine that isn’t a big surprise to you, given what you know about me and my affinity for and protectiveness towards Nature. So many exquisite lines.

“Fish hook, fish hook, fish hook: a necklace.”

“…and when I choose / the field, it disappears inside the bodies of the grasshoppers / and when I choose the pool, he fills the chlorine with carcasses of bees / and when he offers me arroyos, he sends angry horses through them…”

So beautiful. I have no question to add, just sheer adoration for your lines.

SW: Thank you! I’m glad the nature element speaks to you. For me, part of the shadow and haunting of the book is in the environment, the things I keep learning about what we are doing to it. How to live amid all this failure to acknowledge what’s happening and failure to do right, and still have hope? I have a new daughter, so I want the world to stay beautiful and intact even more now than I did when I finished writing the book. My stakes in it are higher. I want her to have gentle monsoons in the southwest and walk on the coasts I’ve loved. I think we have to understand the mystery of the world or we won’t want to save it. We have to want to be lost in its moments.

MA: Yes. I find it hard to comprehend sometimes how someone who has a child–or, you know, breathes air and drinks water–doesn’t come around to environmentalism at some point. Maybe the problem feels too big to grasp and so gets willfully ignored.

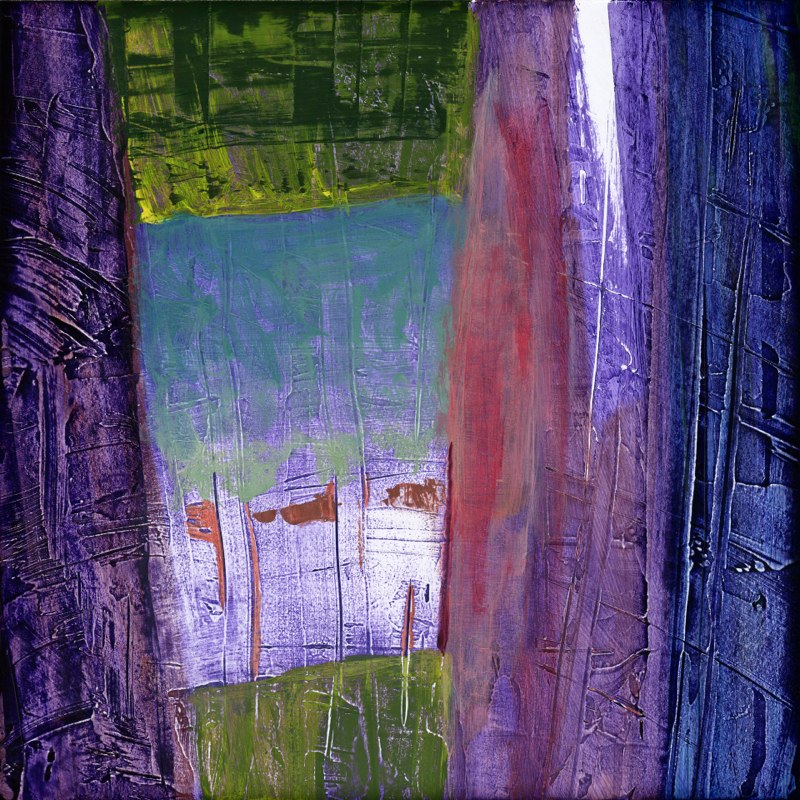

The cover of your book is stunning. Texturally appealing, even. It speaks to me and makes me want to open it. Did you have any say in your cover art? Did the designers get it right the first time? Or did Failure intrude on the early attempts?

SW: I was very lucky. The publisher was really open to suggestions for the cover. I gave the designers a set of images that appealed to me, and told them which were my top three—and this was one of those three. But I didn’t know for ages which image they would pick and what we would be able to get the rights for. Somewhere along the way without realizing it, I started picturing the book with this image whenever I thought of it. When the email came with potential covers, even before I opened it, I’d decided if this image wasn’t there I’d try to fight for it—but there it was.

The cover—which comes from a series of Ellen Grossman’s—felt exactly right to me. She talks about being influenced by cartography, topography, land masses, water currents, etc. You can’t see it on the cover of my book, but she also records the date and time at the start and end of each line—so each one is a little journey. My characters are often in the desert, looking at mountains and maps—so these images fit that. But the characters also have a ghost life in Siberia/Antarctica—and the image also felt right for icebergs and the sea. It allowed me to feel like a setting was being made for the readers without building anything literal that gets in the way of their discoveries of space through the work. I like that people have said it looks like gauze, or a dragon. I like that it’s amorphous. Failure is a Protean character in the book, often trying on new costumes, new forms, so I like the idea of the cover being directive and ambiguous at once. Plus her blue in this image is gorgeous. I could live in that blue.

MA: That is an exquisite, rare blue. When I read your beautiful poems, I feel like I’m seeing something rare, something exquisite that I haven’t seen before. It feels like work so deeply intellectual and yet also so deeply somatic that I fall in love sentence-by-sentence. Keeping in mind what we’ve talked about here, whom else would you suggest I read for something in a similar vein?

SW: That’s such a kind thing to say about my work—one of those compliments I cross my fingers is true about the work in the world—since little would make me happier than having balanced well the head and heart and body. I’m also always scared that I wear the people who have influenced me on my sleeve, so I’m glad it’s maybe not as transparent as all that. Try Anne Carson, Claudia Rankine, Matthea Harvey, Mark Strand, Zbigniew Herbert, Eula Biss, Laurie Sheck. That’s probably good enough to start with, right?

MA: Thank you! A reading list is a gift that keeps on giving. And finally, because we are a recovery-themed journal, what does “recovery” mean to you?

SW: Is it too simple to say finding a way out of failure? Finding a way to peacefully live with failure? It’s part of what this project is borne out of. How do we as Frost says “back out of all this now too much for us”? We have to make peace with our public and private histories without trying to make them disappear— and without making a museum out of them. I don’t have a full way to talk about this yet, but I think recovery also must contain forgiveness. At some point, maybe I’ll start writing about the seven modern virtues. I think forgiveness must be one of them.