Mary Akers:Thanks for agreeing to talk with me today, Anne. I’ve been looking forward to our discussion.

I loved your short piece “The Lemon Method.” It was one of those that I read and instantly knew that I wanted–before any other journal had a chance to snap it up. (Yes, editors can get greedy over the good stuff.) One of the strengths for me was the use of sensory details. They bring it to life. My mouth salivates when the text talks about salivating. I smell the disgusting lunch, feel the feet under the table, hear the troubadour, pucker over the idea of the lemon. How important are sensory details for you when you write and how do you work to incorporate them?

Anne Elliott: Thanks so much for your kind words.

I think sensory detail is the main universal trick of fiction writing. The easiest way to convey a mood is through description. So it becomes almost a habit to just inventory stuff. Sometimes it gets list-y. Then the problem becomes deciding how many items to put in the list. You never have to name an emotion if there is stuff around for the character to perceive.

As for the specific mood of this story, I really wanted to convey irritation. There’s something so taboo about being irritated over Doritos and loud chewing after people have lost their lives. The real-life moments on which the story is based were not irritating, not exactly–the Russian gals in the conference room were excellent company, and our long hours swung from extreme sorrow to extreme mirth. But those extremes of feeling have been so deeply explored (by myself and others) that I wanted to play around with something more quotidian. The impatience of the everyday.

MA: “The impatience of the everday.” I like that.

Lately, I’ve been very interested in things that blur the genres of creative work and artists who work in various forms either before writing or concurrently. I know that you have been a visual artist as well as a written-and-spoken word artist and I have a background in the visual arts as well. Would you like to speak a little bit about the idea of creative crossover? Do your different genres and art forms inform one another?

AE: This is a tough question for me because most of my creative life has been practically accidental. I’m a workaholic, to be sure, but I never, until very recently, felt the kind of focus one needs to get anywhere in a given art form. (And by “get anywhere,” I mean grow artistically. The public life is secondary to me.) I have, in the past, had trouble choosing a path. Fear of failure is a big part of it. Setting up a plan B is part of it. But now I call myself a writer. It’s official–I’m saying it here. I don’t call myself a visual artist any more. But I’m proud of the art I have done, if only for the experience of hands and mind.

My visual art (sculpture, primarily) was always pretty narrative anyway. I was a conceptualist. I spent years in my twenties covering stuff with a skin of writing. Walls, floors, furniture, mirrors, books. I would whitewash everything, then write in black china marker. A stream of memoir, no punctuation, all caps. It looked like wallpaper. Walking into an installation was like walking into an internal monologue. Often, I would wear a white lab coat (written-on) and do stuff like stand on a bathroom scale (written-on) and read aloud from a romance novel I had painted over and rewritten. I should digitize the video. Some of it is hilarious (both intentionally and accidentally). There are things I miss about the eighties. We were so serious with our ideas! Or, was that just a marker of the age I happened to be?

Anyway, this reading-aloud thing evolved, and I fashioned myself into a writer. When I moved to New York in the early nineties, I got into spoken word because there was simply no room in a Manhattan apartment to be a sculptor. I learned to love writing and performing. It got me plugged into a warm community and pulled me out of my comfort zone. I did drawings on the side, but they were primarily a supplement to my writing. Illustrations for my poetry. And then I started publishing hand-sewn chapbooks, for which I designed linoleum print covers. Had to do something with my hands.

It dawned on me recently that I did one group of drawings concurrently with the composition of their accompanying text, and that the drawings might have informed the text as much as the text informed the drawings. I wonder if drawing, for me, is a way of exploring motif. Working nonverbally–the bodily aspect of it, the pen moving across the page, repetitive and non-repetitive movements–can bring language into clearer focus. Maybe that’s how the brain works. So maybe drawing helps my writer self with motif, the way walking helps me with cadence, or listening to music helps me with syntax.

MA: That sounds brilliant. I would love to see that video! (I’m a product of eighties art school, too. I do remember those performance pieces the most.)

I understand you are also a knitter. Margaret Atwood knits. I consider that good creative company. Would you like to say something profound about the similarity of process? About the stringing together, the knitting of words into a story?

AE: Good company indeed!

I knit and crochet improvisationally. I have no plan. Halfway into the project I decide what I’m making. I do elaborate technical experiments, then end up unraveling them or sticking them in the drawer. I chastise myself for my own ambition. Half the garments I make end up unworn. I rarely finish something big, like an afghan. I have trouble getting around to putting buttons on a sweater. Sometimes I quit altogether for months at a time. Then I pick it up again and it’s like an old friend. In all these ways it is just like my writing.

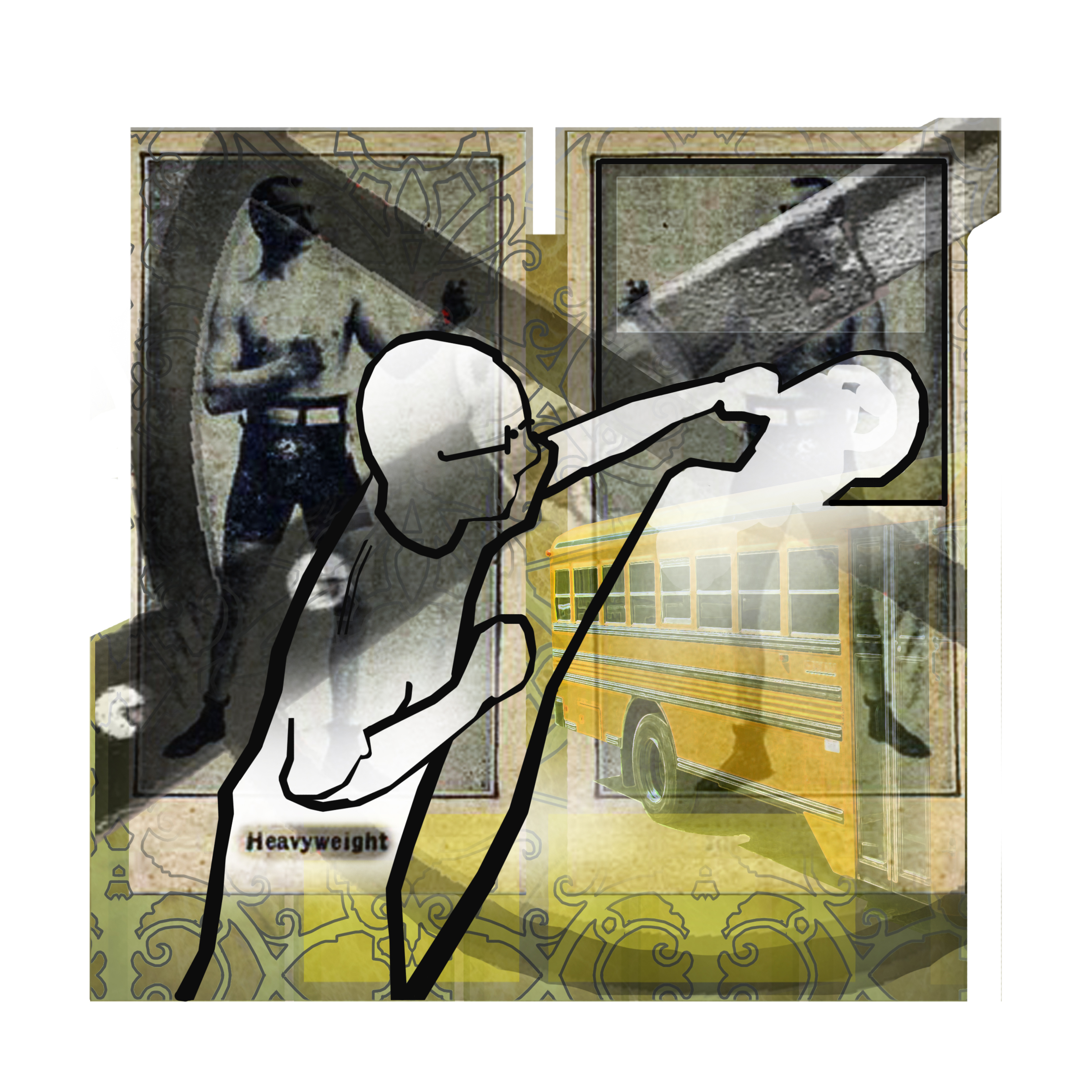

MA: You reacted strongly to the image that Morgan Maurer made for your piece. I really liked it a lot, too. Could you tell us a little bit about your reaction to his work and how it affected you?

AE: Well, I’m predisposed to like his work because he went to my husband’s alma mater.

But beyond that– I love what he did with the ornate pattern overlay in all the illustrations. It reinforces the flatness of the picture but also gives us a sense of layering. The way stories are layered. As for the one he did for my story, I just hand it to him for tackling the subject matter head on. The World Trade Center can be such a visual cliche, and he managed to avoid that trap, by making the “towers” into abstract stripes running through the picture. The yellow sunburst is like an explosion but also a lemon. And there’s a haze to the picture that conveys a mood.

MA: Yes, a sunburst and a lemon. Brilliant.

And here comes my old standby question. What does “recovery” mean to you?

AE: I love the 12-step notion of acceptance, where you have to work to recognize your own part in the drama. There’s a loss of innocence that happens when you look at the way things really are. It’s heartbreaking. It’s angering. Sometimes you break your own heart. Sometimes fate does the job. You have to figure out what to do with the heartbreak and anger. But the recovery piece of it involves the cultivation of a new kind of innocence. Being open to the possibility of beauty or humor or warmth, in the midst of learning to accept the unacceptable about yourself and the world.

It takes practice, to be open and base that openness on reality, not delusion. That’s what I mean by innocence. There’s the innocence you’re born with, but also the innocence you learn. The first one is dangerous. The second one is not.

This might be one reason I’m so drawn to realism in fiction. Emotional realism, I mean, not necessarily literal realism. Taking a hard look, losing and finding innocence, changing one’s judgments–reading and writing fiction facilitates all these endeavors.

MA: Wonderful. Thanks so much for talking with me today, Anne. I just knew it would be a fascinating conversation. And if you get that video digitized, I promise to link to it here. 🙂