Sara Michas-Martin: Reading your essay “New Miserable Experience” I was struck by its raw, emotional truth. The honesty was punctuated by your choice to evade a tidy conclusion. The reader is left tangled in a moment of internal conflict, a feeling of unrest we understand that is ongoing for Bobby (and Billy, too). Can you talk about the process of writing the essay and how you were able to manage what I imagine to be difficult feelings around the subject matter?

Robert Fieseler: Sure, Sara. You know I love your writing, so thank you for the kind words. When you write about family, it’s brutal. You’re writing about people you know in their innermost sanctums: their homes, their heads, where we accidentally drag back the bullshit of the world and use it to wreck each other. It’s you and your loved ones at their most vulnerable, unguarded, screaming at each other, refusing to wash the dishes.

So I sketched the first draft of this essay in my head in the minutes after my brother finished his Step 9 “amends” and left the house. This was December 2012. The scenario was fresh and I saw the way to write it like a path through a very old forest. I was sitting alone at the kitchen table–where we’d gathered as children–and I felt something very hard to express.

The cloud of feeling was something halfway between being demolished and being pushed against a wall. I think a very old part of me, one that resists logic and loves to tear me down, believed I did this to my brother – that I’d never fully wanted a Billy in my life and that I’d tinkered too much through our competitions and created the void he filled with addictions. I’d messed with his wiring. Writing this piece could mess with mine.

The mercenary in me knew this could be interesting material to plumb. I tend towards the confessional as a writer, and the confessional – as a formula – finds its legs in inner conflict. In the merciless description of what is. You go for the fucked up. You write about fucked up things and untangle the knot for the reader. Voila! I think confessional writers get good at exploiting this murkiness and writing their way towards an answer. Not THE answer but AN answer.

So I had the choice to write and face the consequences or not. The consequences could be embarrassing my family, harming my brother as he attempted to get healthy, putting myself in a psych ward or even ruining my young writing career through a revelation I couldn’t live down. OR…I could try to figure out a piece of what was true in a confusing moment for the both of us. I could try to parse what was real in between all the family myths and egos and my delusions of grandeur.

I clearly chose to write, though I didn’t know when I started what would happen as a result. I risked the honor of my family. I think I got lucky. My brother and I actually became closer through the long process of writing the essay. But I’ve spoken to other writers estranged from family members as a consequence of putting pen to page. I can’t figure out what makes it break towards celebration or disaster, what makes people react the way they do when they read about themselves through the eyes of a writer.

Several people have asked me how Billy is doing. He’s almost four years sober now, married, with a tech career and a townhouse. Solid guy. Mows his lawn, walks the dogs. He’s one of the best people I know. The truth is I barely knew him as a man before I attempted to write this. In a sense, I ended up writing out of my own head and into his.

SMM: Can you talk about your choice to structure the essay in five sections, and moreover, your choice to present your brother’s perspective as well as your own? I am curious about your process in arriving at a final draft. Was the occasion of meeting your brother always the entry point for the essay?

RF: I was attending the Columbia Journalism School in New York City when Billy did his Step 9 with me, so I approached the essay much the way a journalist writes a feature story. I also approached the writing with the ethics of a journalist, which means the story had to find fairness and balance among its subjectivity. It was the only way I knew how to write. A journalist gets a whiff of an opening paragraph, the world in micro – me mistaking my brother’s list as good – and then expands from that micro to a macro statement through what’s called a “nut graf” – my simple mistake revealing a larger, pathological need. It’s a narrative trick, one journalists use all the time. This one bee reveals all bees. This hurricane, a hurricane season. This student’s experience, a trend.

From the initial nut or point of expansion, I created a mental outline to guide me from sentence to sentence, beat to beat. I wanted some of our quick dialogue. I wanted to set the scene with the Christmas decorations. I wanted flashes of memories informing the present. The rest I let happen more intuitively. When I write, I tend to have a plan but only enough of a plan to let the story unfold. To let it get weird.

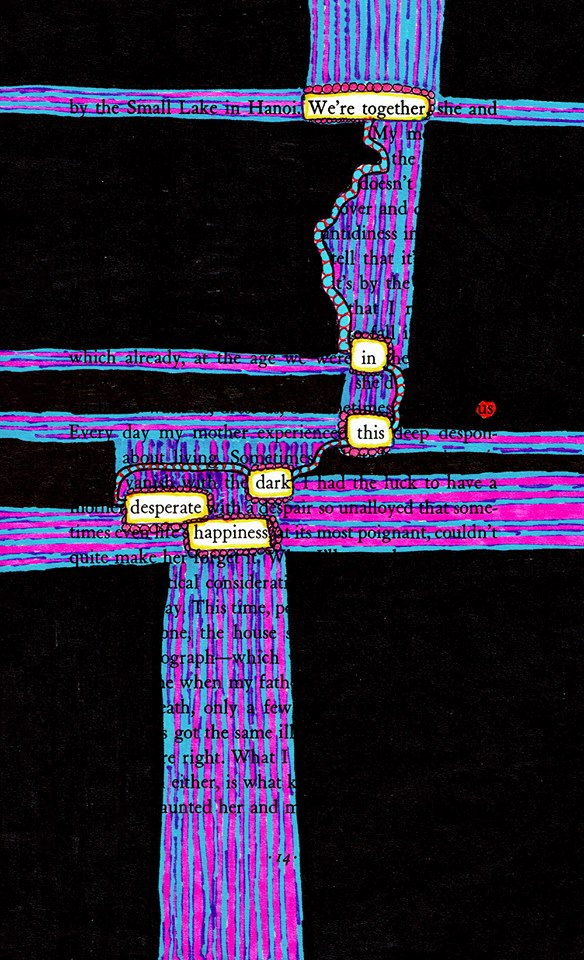

I wrote my section in the first person. Journalists tend to use what’s called an “objective narrator,” which closes off the internal world, but that would have been dishonest in this case because, as they say on the playground, my epidermis was showing. I knew that I wanted the two brothers from two equal vantages – to explore a larger theme of rivalry – but I didn’t expect to write Billy from the first person after I wrote myself that way. I didn’t know if I that was allowable. In journalism, changing first-person is pretty much verboten. An editor wouldn’t stand for it.

But I’d given Bobby the first person treatment – by this point, I was thinking of myself as just another character – and I noticed how the first person slanted the reader towards Bobby’s picture of events. This slant revealed bias, and a bias is a blind spot, a convenient instance of fudging or overlooking the facts. It seemed clear to me then that I needed to re-weight the story based on what I’d revealed through Bobby. I didn’t know if I had the literary muscles to write through the eyes of another human being – pure journalists, generally, don’t put that ability to practice – but I thought that if I could do this for anyone, I could do it for a person who shared a bedroom with me growing up.

I found myself fascinated by Billy’s emotional state just before he entered the room to confront his brother. In a Step 9, the amends can often come off as rehearsed, because the amend-maker actually has rehearsed the apology. But the time just before the Step 9 would be raw, improvised, anxious. I thought the tension between those two states could be revealing and evoke sympathy for Billy as a character.

I didn’t set out to mess with time–to have Billy always catching up to the action in the conversation–but the timing thing just happened. And I needed a Billy reaction that summed up trying to catch up with Bobby, who’s running ahead as a way of eluding the confrontation. So I let Billy nail it in a second section that reveals Bobby as an unreliable narrator about to discover something by stumbling into it. The last line I wrote was the combined fragment that took about two years of paring and examining to reach: “He did it with booze, I did it with winning.” I hope the story and structure reveal that Billy had less of an agenda in our interactions that day.

SMM: How does your relationship to journalism differ from your relationship to creative writing?

RF: They inform each other. Great nonfiction writing is founded on great reporting, on the application of interview skills and sleuthing, archival research and document requesting, deductive reasoning and questioning what really happened in a confusing event from multiple angles. From this data set, one then assembles the Venn diagram of a likely truth, out of all possible likelihoods. It’s a picture of reality as it moves. This isn’t the Truth with a capital T – only God knows that – but it’s the best possible narrative assembled from evidence. It’s the best tool we have as human beings to figure out what’s going on.

This piece was originally a reported memoir hybrid. I’d have more things happening in a fictionalized account. I’d have us moving through multiple rooms, perhaps upstairs into our old bedroom. I’d have poignant photos from other eras of our lives, which we don’t see because they weren’t there, but now up on the walls for the main confrontation. I might have his fiancée out in the car. I might have him punch me and break my nose to look like his. Isn’t that poetic? But I’m not a fiction writer. I believe Bryon when he said, “Tis strange – but true; for truth is always strange; Stranger than fiction.” Byron lived a weird life. Life is so weird.

So I had to interview Billy. We were still estranged, and I conducted this interview via phone almost immediately after I came up with the outline at the kitchen table. I had to get him when he was fresh and ask his permission to research and write about his Step 9. I think he was surprised to get my call, then flattered, or at least hopeful that I seemed more interested that I’d been during the actual Step 9. He agreed to help. I had to ask him about what he was doing before and after the experience. I had to ask him how he prepared to talk to me and why he was nervous. I had to ask to review his Step 4 journal, where he conducted his fearless moral inventory. It’s a very private document.

I had to ask to review his Step 4 page for me. I still have it. It’s awful. Not that he wrote those things about me. Billy had to be fearless in this regard to get well. It was just awful to read about myself from that vantage – I was sick, but in a way that society rewarded: I won, and they cheered. I received accolades that spiked my brain chemistry. I chased the dopamine hits, like Billy. Reporting this stuff meant a commitment to discovery on my part, and such a commitment has a price, a psychological toll. We all pay the piper this way as writers. I’m not going to lie. I cried a lot. I don’t know why the reporting facilitated tears I did not have in front of him, but it did. And I chased the story to get it right. I chased it through myself, through him, through other family members, for about two years of reporting and writes and rewrites.

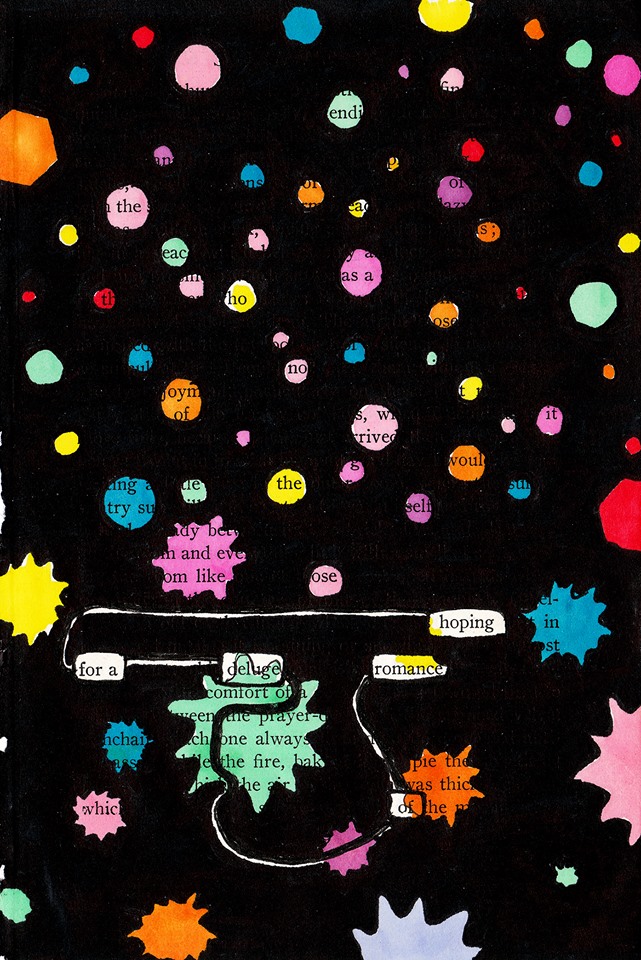

A story, fully formed, I find, is often smarter than you are. But you have to blunder and chase it down like Wile E. Coyote with the Road Runner. And, this will be metaphorical so excuse the flight of fancy, the story will eventually turn back and notice you chasing it and ask for a toll. And you pay it or you don’t, and the end result is likely the difference between a meh or a noteworthy piece. You have to risk yourself. A journalist will give something small, like a piece of mind. A thought. Sometimes that’s enough. Some risk nothing and still come off pithy, clever; these are the Chandler Bings of reporting. A creative nonfiction writer will offer a vein or, sometimes, the heart. And to be torn up from the heart hurts, but then the writing makes you somewhat whole again because you got to be, temporarily, the vessel for the thing you were chasing. You got to speak its name. But you have to decide whether it’s worth it. You will not be the same afterwards. There will be consequences to what you realize. And you will need to change your life as a result of realization or be a liar.

SMM: I first met you years ago when you were an undergraduate. Can you talk about how your relationship to literature and writing have evolved in last 10-13 years? Have there been specific books or authors that remain influential? What’s the most exciting thing you’ve read in the past year?

RF: I read The New York Times every day. I have for years. My grandfather could make a day of the Times. Great journalists, great feature writers – like A.A. Gill of The Sunday Times or Buzz Bissinger for Vanity Fair or Gene Weingarten for The Washington Post or Erika Hayasaki wherever she writes – fashion grammar-perfect sentences that curve into each other like great woodwork and gleam with a kind of simplicity. Most of these journalists also write books. These authors can arrange words in a way that gets two points across – the person, place or thing itself, and then the larger significance.

I always wanted to be able to do that. I guess when you met me all those years ago, I didn’t know how to yet. I wrote poetry that struggled sincerely, poems filled with lyric moments, poems that didn’t really want to be poems and therefore didn’t work. It took me a long time to figure that one out. I worked really hard on those poems, on being a “serious poet,” but I just didn’t love those words as much as I loved others.

I couldn’t write prose yet, but I could weave narrative moments that showed promise. During this whole process of realization throughout my twenties, I was reading Nabokov, Amy Hempel, Vonnegut. I read Emily Dickinson. I read Yeats. I read the Beats, all of them, then Truman Capote. Toni Morrison. Salman Rushdie. Saul Bellow. Not whole catalogues, usually just one or two works.

Then one day, I was listening to NPR and heard a story about a class at the Columbia Journalism School called the Book Writing Seminar, to which journalism students had to apply separately after being admitted to Columbia. I mean, the double gate, right? I’d never gone to an Ivy League school. To think there was another barrier of entry! Through Sam Freedman’s guidance, these students had entered with fledgling projects and published more than 40 books. The story’s still available online. I heard Sam’s voice for the first time here, and he sounded like someone who could kick my ass, and I knew that his class – if I could swing it – would be my proving ground, the place to become a real writer.

I applied. I got accepted. And it’s taken a long while for me to find my legs as a writer and nonfiction author. You’ve caught me in the midst of writing my first book length piece of nonfiction for the Liveright imprint of W.W. Norton, which is daunting, and I’m learning how to sustain a long narrative for the first time. Just get better every day, I tell myself. But the slow progress can be maddening. As Sam Freedman says, “Do the work.” Pay the price. Most people can’t take the hit – the idea that they have to be better than their ceiling – or they simply can’t lose the lifestyle they were enjoying.

I read classics these days. Thomas Hardy. Bronte. I’m rereading Walden, by Thoreau, cover-to-cover, and am entranced by his mentions of the railroad and industry. Before bed, I read a paragraph from Leaves of Grass, because I find that I have fewer nightmares. Whitman has a way of seeing the good in others and in the American experiment. I get too many literary magazines, from all those free subscriptions with submission to their social lottery competitions – who knows how you judge something so subjective – but once in a while I do read a story that consumes my thinking, the most recent being Nina Boutsikaris’s essay in the Winter 2016 issue of Redivider called, “I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry.”

My favorite book continues to be A Farewell to Arms. It sets you up and then buries the knife, and I bawl my eyes out. On an emotional level, something like that happened to me when Billy left the house, and I tried to portray that in the essay’s final montage. Maybe it worked…I’m still figuring that out. I like the fact that there’s always more to read and learn. I haven’t even cracked Proust or Tolstoy (scandalous, right?). But writing this essay helped me become less a stooge of ambition. It taught me that winning, that ambition, can harm the people around you – it played a part in harming my brother, and I’m consequently less of an outright striver, now only striving to be less of a know-it-all in my life and in my words.

Sara Michas-Martin writes, teaches and designs. Her book Gray Matter (Fordham University Press) was chosen for the Poets Out Loud Prize. Her poems and essays have appeared in the American Poetry Review, The Believer, Denver Quarterly and elsewhere. She taught a very young Bobby in 2002 at the University of Michigan’s New England Literature Program before becoming a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.