The old man doesn’t work in the store, but that doesn’t stop him from suggesting the watermelon. He could be an older employee. In hard times a job at a grocery store doesn’t seem so bad. But that isn’t the case. He doesn’t work at the store. The state of his fingernails is what gives him away, yellowed and bitten to the nub. He doesn’t wear the red vest of the other employees but that could be written off as a minor error. Maybe he forgot to put it on this morning. The fingernails do it though, they give him away. No one would employ someone with such negligence for basic hygiene. Still, he pursues customers with gusto, his gray combover flopping up as he trots after them. It doesn’t look like his combover has been combed over in quite some time, but the evidence remains. They don’t want the watermelon. They scurry away from him as if from a dog with rabies. The old man falls down chasing after them and a look of sheer terror crosses his face. He is concerned about the watermelon. He inspects it from the gray-speckled tile floor and is relieved to find it intact. He stands up and is smiling. He’ll find someone else to take it.

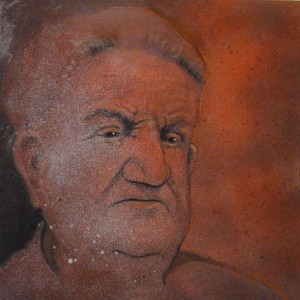

My own father never really cared for me. That’s not my phrasing. He said that to me at one point in time, which made his diagnosis difficult in an untraditional way. When the doctor said, “I know this is difficult,” he wasn’t referring to the fact that my father and I never got along, and that his condition was going to force us to spend time together. He was talking about the disease. As I am a man, the doctor most likely didn’t question the lack of tears on my part, but he didn’t know. I didn’t have any tears. The man had made it clear to me that he wasn’t interested in being a part of my life, and now he needed me to be. He needed me to be a part of his life, or his life would be over sooner than preferred.

I did have tears the first time a boy broke my heart, but dad wasn’t interested then.

“Will you hand me my jar?” he said. He meant his beer glass. It was the collector’s type that restaurants sell. I never saw him with another one so I guess his collection ended at one. The restaurant label had long since worn off. He didn’t even use it to drink out of; he used it as a spit cup for his chewing tobacco. It was a disgusting habit and I hated it. I handed him the glass.

“Did you hear me? Louis said he wants to see other people. What does that even mean?”

“That’s just how your type are,” he said, and spit a large glob of brown juice. He was not a caring man.

The old man has caring eyes. It’s clear to everyone that his mission means everything to him. He has nothing on his mind but making sure this watermelon gets eaten. It’s too perfect not to be. Every once in a while he puts it up to his ear and taps it with his knuckles. The look on his face afterwards is one of pure contentedness. He worries from time to time that the fruit might be getting overripe, but each time he finds that it isn’t is a little bit sweeter than the last. Some part of him must be aware that if he doesn’t get someone to take the watermelon it will eventually be overripe. I’m in the frozen foods section when my turn comes. I can see him casing me from near the lima beans. He holds it in his arms and buffs out a perceived spot with his shirt. I notice it has a mustard stain on it near the collar. He’s looking to see if I’ll take good care of it, if I’ll slice it properly. A poorly sliced watermelon can be ruined. I’ve got to be the right candidate. He doesn’t speak to me when he approaches, but holds it out to me.

“No thank you,” I say, but he doesn’t understand. He holds it out but I keep pushing my cart towards frozen pizzas. “It does look good,” I admit. “But I don’t really eat watermelon. I don’t need one.” He nods but his face doesn’t change. He doesn’t understand. He hangs back but I can see that he is still following me. Apparently I have been chosen as the rightful buyer. Or maybe I’m just the first person who hasn’t run away from him or told him to leave me alone.

Bittersweet. I was ashamed to admit it, but it was true. My father’s condition was bittersweet. He was no longer the same man, but it was difficult for me to mourn the death of my father’s lifelong personality. This new man who had appeared—he liked me. He needed me, and he appreciated that I put his jacket on for him before we went to the park. It was amazing how fast it happened. It wasn’t fast strictly speaking, about average the doctor had said, but the change didn’t seem gradual. At first he forgot a few things here and there, but he was still the same man. When Marv came with me to check on him, he would ignore him completely and have a terse conversation with me. The funny thing was that had Marv not been there, we probably wouldn’t have had any conversation at all. I don’t know what he got out of it. Maybe he thought he was proving something to Marv by ignoring him. Those were the days before Marv and I moved into his huge old house. He still resented us checking up on him. He only cursorily acknowledged that it was a safety issue and permitted to me coming by once a day in the afternoon. He always pretended like he had been doing something so important that it couldn’t possibly be interrupted for very long. He had to fix this, or he had a program coming on in five minutes, or he was reading a particularly good piece in the paper. Anything to make my visits as short as possible.

“You read this one?” he said to me one afternoon a few years ago. He was holding up a newspaper that I recognized. I set my bag down on his kitchen floor. “Jesus, don’t put that there,” he said. “You’ll scratch up the floor— put it on the damn hook.” I did as he asked.

“What is that dad?”

“New zoning law. Bullshit if you ask me. Gonna knock down my Arby’s.”

“What day is it, dad?”

I had a set of questions the doctor told me to ask if dad ever got confused. They weren’t exactly scientific but they could give me a pretty good idea of his state of mind. The first test was how dad reacted to the question. He gave me a suspicious look. He was angry but cooperative.

“Monday.” I didn’t respond. I waited for him to elaborate. “The fifth.”

“What day is on the paper?”

He looked down at the paper in his hands and it was painful to see the look on his face as he realized that he was holding a paper from three days before. He had already complained to me about the knocking down of his Arby’s. This was the first wake up call. He yelled at me and told me to leave. He was fine and wouldn’t be needing my services for the rest of the day. That evening was the first time Marv and I had a conversation about dad’s future. It was the first time the possibility of us moving into his house had come up. At that point in time Marv and I didn’t even live together.

“Okay dad. I’ll go. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Pick up your feet. Your queer shoes are scratching up my floor.”

He tails me through soups, both canned and boxed. I prefer the boxed kind. He doesn’t pretend to be shopping. He doesn’t have that kind of tact. He mutely follows me wherever I go, waiting for me to show him some sign maybe—a sign that I’m accept the watermelon, that I’m worthy of it. It’s clearly the best one of the bunch. When he gets close enough I can tell that he needs a shower, but that’s only for small moments. He mostly hangs back. That is until I get to coffee. I stare at the coffee every week, like I’m going to change my mind, but I never do. I always get the same kind of coffee, but the staring at the selection of coffee is a vital part of the shopping experience for me. He gets closer as I marvel at the different varieties of beans. It seems that there’s a new kind of coffee every week. The coffees are like my news. I don’t watch the news and I don’t read the news, but I’m very up to date on the coffee world. You mean you haven’t heard about the strife in Guatemala? No but their coffee beans have doubled in price in the last month. Now I know why.

The coffee aisle is always the last I visit. Maybe he can intuit that, or maybe he’s seen me here before. Either way he can tell that I’m about to leave, and he doesn’t want to lose another one. He comes directly up to me, avoids eye contact entirely and places the watermelon in my cart. I don’t get mad. I don’t yell at him. It is a good watermelon. And he was careful not to damage any of my other groceries. He placed it down gently next to my bread, making sure not to damage any corners.

“Thank you,” I say. “It looks like a winner.” I rap my knuckles on the fruit and am greeted with a satisfying hollow noise. “You picked out a good one.” He walks away without saying anything to me.

“Thanks,” I call after him. I hear him mumbling to himself as he slides out of view and back towards produce.

“It won’t be a problem. Trust me.” I tried to reassure Marv. It was his first time going back to my dad’s. The first and last time he had come along hadn’t gone well. “He’s not the same. If he had the capacity to realize who you were, he probably would still hate you, but he doesn’t. His disease has lessened his prejudice because he can’t really distinguish people apart enough to discriminate against them.” My easy way about dad’s disease made Marv uncomfortable. We were going over to look at the space more than to see dad. I’d basically been living with him for a while. I left him with a neighbor I’ve known since childhood to get Marv. My pile of blankets were folded on the couch, and my reading glasses on the arm. Evidence of my living there were everywhere, greeting us.

“Doesn’t seem right,” Marv says as we approach the front door. “Appraising the livability of his house.”

“I can assure you that it won’t bother him. He’s mellowed a lot. Depending entirely on other people will do that to you I guess. I think he might have even forgot that I’m gay.” That gets a chuckle out of Marv and we enter my father’s house.

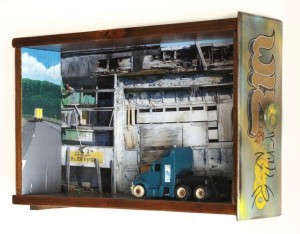

Marv is a contractor and took notes in his pad about the problems the house had. Over the past few years it had seriously declined. With dad no longer being able to make repairs (I took away all his tools for safety) and me being incapable of doing them in the first place, a lot had gone unrepaired. There was a leak in the attic. That was to be number one on the list. There were bugs in the basement, and the garage was full of old newspapers. Dad never threw away newspapers.

“I use ‘em to start the fires in the fireplace,” he used to say, as if he needed a thousand pounds of old newspapers for the three fires he lit each winter. Countless light fixtures were missing pieces that had fallen off or been knocked off years ago by a still angry, ashtray throwing dad. He loved the Phillies. But like me, they were a constant disappointment to him. I still put the games on for him, but he got frustrated when he asked me the names of the players and I couldn’t tell him. It was actually nice, his quiet frustration. He crossed his arms like a child and pouted. It was endlessly more pleasant than him berating me for never taking an interest in sports.

The guilt was hard at first, but wore off. What did I have to feel guilty about? I was taking care of a man that had never liked me—had told me so to my face, had not attended my college graduation, and publicly condemned my “lifestyle” when it was his turn to speak up in church. But still I felt guilty. I liked dementia dad better than regular dad. That’s not how it was supposed to be. I was supposed to feel sad when my father succumbed to a degenerative disease, and no longer consistently remembered who I was, outside of the person who took care of him. I often wondered who he thought I was when he would ramble on about the Phillies to me while I changed his diaper.

“My son never went to a Phillies game with me,” he said one time. That was the first time I really understood that he didn’t even know me. But what confused me the most was why he didn’t question it. He had reverted to childlike status, and children don’t question authority. I told him to do things and therefore I was in charge. He yielded to that instinctively. So he didn’t question the middle aged man changing his diapers and cooking his meals. I was just there.

I’m standing in the checkout line behind an obese woman who has at least twenty items, twice the limit of this line, when I see him again. He has picked out another watermelon, and is offering it to an old woman. She is hunched over and clearly frightened by him. She is motioning for him to leave her alone, but he doesn’t understand. He has chosen another perfect specimen and she should buy it. I don’t know why I just watch and do nothing. I can predict in that moment everything that is about to unfold. As sure as I know that Yuban columbian is six cents more an ounce than my preferred Master Chef medium roast—I know how this is going to end. She yells and pushes her cart at him. They both fall down. Another shopper rushes to help the old woman up. The cop standing by the front doors takes action. He runs to the produce section, holding his belt buckle. The watermelon is smashed on the floor and is all over the old man’s shirt, obscuring the mustard stain in a sea of red. The man stares down at his broken baby and bursts into tears. He tries to wipe his face on his shirt but only makes matters worse. His tears run red with watermelon juice and the cop hauls him to his feet. I should say something but I don’t. The cop turns the man around and cuffs him. For some reason this cop can’t see that this man doesn’t belong in prison. He doesn’t know because he was standing by the automatic doors reading his newspaper, bitching about zoning laws. How they’re making his Cracker Barrel move to a different location, farther from his apartment. The building’s going to be a dance studio. He leads the old man out of the store, pushing him from behind. The old man stumbles and we make brief eye contact. I grab the watermelon out of my cart to hold it up for him—to show him that I’m buying it, but it’s too late. The Cracker Barrel cop has already pushed him out the door. I’m left holding up a watermelon in the air in front of confused shoppers. One man claps, but quickly stops when he realizes that this isn’t one of those types of moments. The janitors have already been called and they’re pushing their cart towards the split-open watermelon on the floor. The janitor’s cart has a radio, and it’s tuned to local news. A newscaster tells of how a new school is being built. Zoning laws had to be changed, he says, and a local video store will be forced to move. At least it’s for the children. The janitor reaches down and takes a little bit of watermelon from the middle. It truly is perfectly ripe. He eats some of the melon from his palm, and spits out the seed, no respect for the dead.

Marv was shocked by the change in dad, like I had been at first. I tried to explain that it only felt like it happened quickly. He didn’t see him every day so the change was more drastic. Because I was with him every day I could chart his changes: the first day with the newspaper, the first Phillies game entirely watched and completely forgotten, the first time he forgot my name. I had a mental checklist.

“How do you deal with it?” he asked me, while taking a sip of lemonade. He and my dad were painting the living room together. Dad had been calling him “Marty” all day, but seemed to be loving the painting. He wasn’t very good at it, but Marv mostly covered up his work.

“I’ve come to terms,” I said, because I couldn’t admit it. Marv felt the appropriate emotions and he wasn’t even the son. I couldn’t say to him, “You remember the man, he hated me,” because that wasn’t the correct response to have. I couldn’t say the truth. He was better now. Marv would have said, ‘That guy was always in there. He was just emotionally closed off. He’s always loved you,” or something like that, but I don’t know if I could believe it or not.

“Eventually he will forget everything. Even who he is,” the doctor had told me in private, a year or so earlier. He hadn’t said he would revert to what he was feeling inside—that he would finally love me, in his cluelessness. That’s not what the doctor said. The doctor said he would forget. And he had forgotten. He forgot how much he disliked me. And I had a hard time letting that distinction go.

I pay in cash and the pockmarked kid does a terrible job bagging my groceries. The cashier makes no comment about me holding a watermelon above my head. I could have forgiven her for doing so. I drive slowly through the neighborhood and look at the Arby’s as I drive by. It still has the appearance of being new. It was a good remodeling job. Marv and I took dad there for lunch on a few occasions. He loved it. Dad died about three months ago. We live alone in his house now.

“What’d you get?” Marv asks me reflexively when I come in the door. He knows I buy the same items every time I go to the grocery store.

“I got a watermelon.”

“What?”

“We’re having watermelon tonight.”

Matt Thompson is a graduate of Georgia College & State University. He lives and works in Milledgeville, GA. He has written two novels: X. And Oleanders in Alaska, both available via Amazon. His previous short fiction has been featured in apt. He lives with his chihuahua Bruiser, and is seeking his MA in literature.

Read an interview with Matt here.