Image first published in Rolling Stone, appears here courtesy of Victor Juhasz

I can’t help you kick

The drug you call pancakes,

Or the replacement

You call syrup.

Your life has been

One long sweet taste

Of drama. You came nearly

Close to finishing

In many ways:

The swig of strong

Medicine. The twists

And burns

Of what and why

You thought

You were and are.

I remember

The night you screamed

At Dad saying

You were dancing

On his grave and to mom

You wished her

Back on the floor

Near the empty

Aspirin bottle the day

Other sister found her.

As a family, we have

Been through the recommended

Books, the last minute doctors

You gave up on moments

Before the truth was revealed.

We have been close

To finding the border,

Crossing over into sanity.

We have sucked it up

And loved you while

The trail of white water

You left behind churned

Up in our wake. At once

We were glad angels

Loaning you money.

At next, we were worse

Than the yellow devils

Of your irises, reflected

Upon us as you stared

Us down into oblivion

When we asked about

The missing tablets.

This is what it is like to live

Inside a struggle,

Just a kiss beyond

A fairy tale destination.

For which there is no middle

Ground, no training wheels,

No prince, no magic potion,

No deep red apple, no sugar

Plum house, no clever mice,

No breadcrumbs, no red hood,

No glass slippers, no pumpkin,

No wild wishing brook,

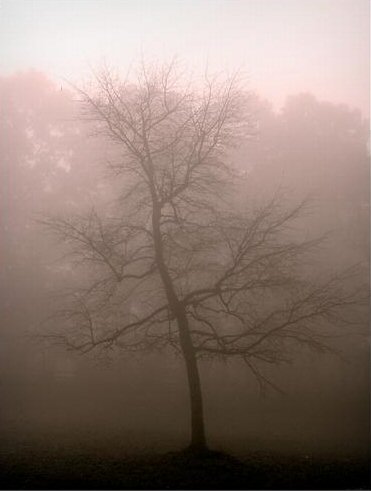

No monster or glass coffin

In your woods.

There is no gate to hold onto

As you swing back and forth.

Millicent Accardi is the author of two poetry books: Injuring Eternity and Woman on a Shaky Bridge. She received fellowships from the NEA, California Arts Council, Barbara Demming Foundation and Canto Mundo. A second full-length poetry collection Only More So is forthcoming from Salmon Press, Ireland in 2012.

Read an interview with Millicent Accardi here.