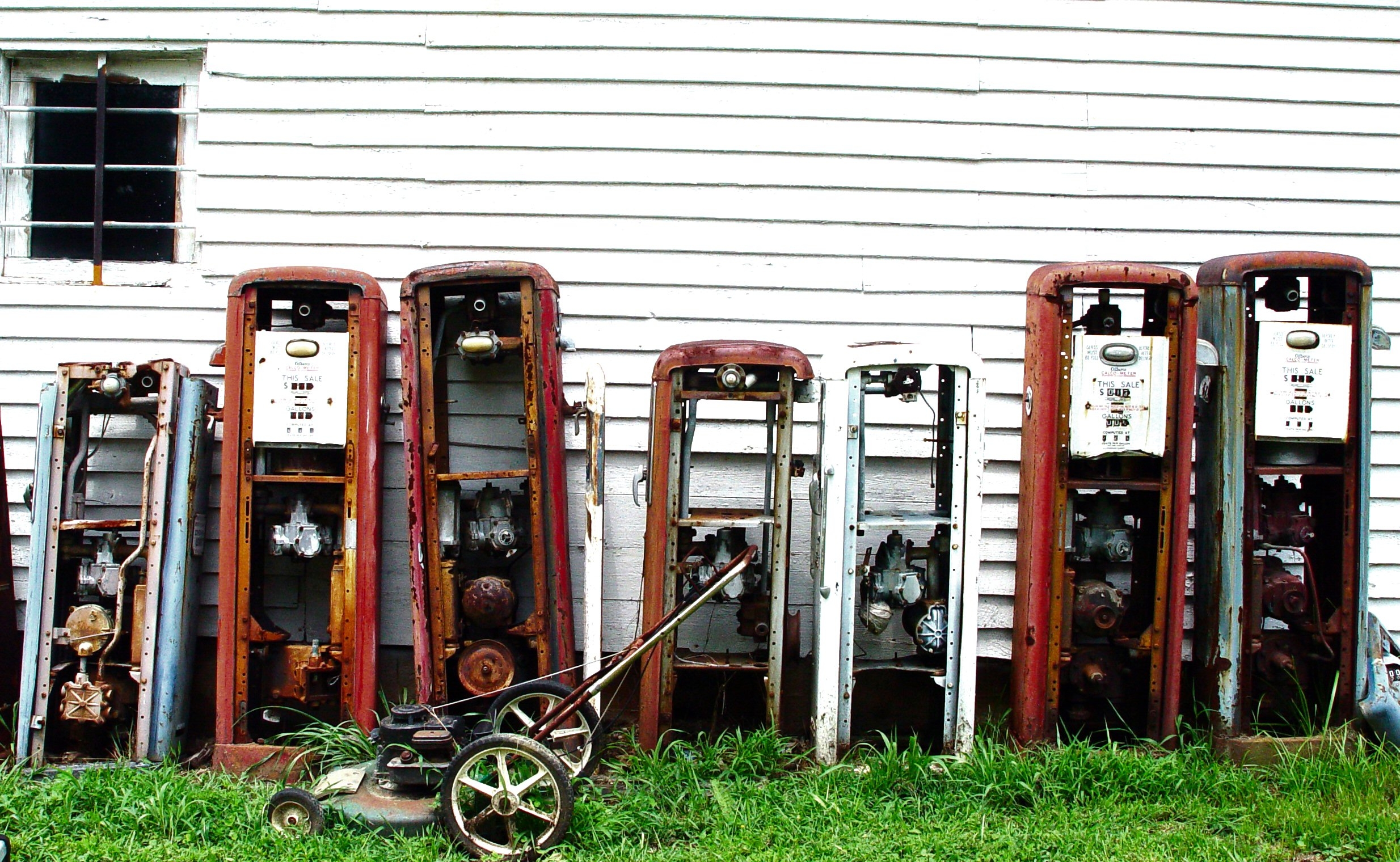

Image by Jenn Rhubright

Sunday evening in the garden, as she reaches into the rosebush, Evelyn feels a twinge in her left knee.

Shifting her weight on the gardening pad doesn’t make a difference. Evelyn sighs, stands up, and tucks the clippers into her cardigan pocket. She is done for now. Shakespeare, presiding over the patch of heather in the corner, says to her, “Go.” Evelyn has been waiting for this sign. The chimes on the back porch chorus in the dusk. The moon casts a soft light across the roses standing tall under Shakespeare’s gaze. Evelyn listens but the sound of his voice has faded and she is alone again. She rubs one hand with the other and looks at the pile of pruned branches. There is so much to do if she is going to go.

With aching knees, Evelyn walks along the stone pathway. Shakespeare’s eyes and unsmiling lips have not moved but the word echoes around her. She rests her hand on his cold head, the band of her wedding ring clinking against the concrete. His head is damp, as if water is seeping from the inside. By this she knows it will rain tomorrow. Evelyn looks forward to the clouds and rain. It will feel, for a few days at least, like the garden she visits in her dreams.

With the sleeve of her sweater, Evelyn rubs the moisture off the base of Shakespeare’s bust. When she is sure he has no more words for her, Evelyn walks inside to the kitchen. A stack of bills sit on the countertop. Dirty dishes wait in the sink. It is no one’s fault, she thinks, rubbing her face. The sounds of the Trailblazers’ game drift from the living room. As Richard dozes on the couch, the cat curled next to him, Evelyn calls Maggie.

“What did Richard say?” Maggie asks.

“Just book the ticket, please,” Evelyn whispers. “I can’t wait any longer.”

Next, Evelyn calls Janey, her daughter, who worries about Richard being alone. That’s why she is calling, Evelyn explains. They are on the phone only a few minutes. Evelyn can hear the cadence of Richard’s breath, his hiccup when the volume on the television grows louder during the commercials. In thirty-eight years, they’ve never been apart for more than a day.

~

Janey was six when they moved into the house. Evelyn claimed the kitchen and backyard as her own and Richard set up the front porch with two wicker chairs, a table and transistor radio. He sat there in the evenings listening to baseball games and playing chess with Janey. On Sunday afternoons, he worked the crossword puzzle and talked to their neighbor, Mr. Keegan.

Evelyn preferred the shelter of the backyard, though her first attempts at a vegetable garden yielded a meager bounty. Janey drifted between them—bringing a tomato or squash to Evelyn then playing chess with Richard until bedtime.

One day, when Janey was twelve, she saw a poster about Portland’s Shakespeare Garden and begged to go. In the middle of an April rainstorm, Evelyn and Janey found Shakespeare’s alcove tucked behind a row of cypress trees in the Rose Garden. Evelyn stood under an umbrella while Janey wandered through the budding bushes writing their names in a notebook.

Each rose bush and flower had a sign bearing the plant name and its origin. Prospero from The Tempest was a tall, spiky bush that in the summer would offer enormous red roses. Fair Bianca from The Taming of the Shrew was a small bush showing just a wisp of the white paper-thin roses to come. A few names sounded familiar to Evelyn—Ophelia, Tatiana—but she couldn’t place them. She hadn’t read much Shakespeare.

Strawberry plants bearing tiny fruit were nestled in the ground between the roses. Janey ate one before Evelyn could stop her. Etched into the sidewalk below a statue of William Shakespeare was the phrase, Of all flowers, methinks a rose is best.

“I don’t want just roses,” Janey declared.

For days, Janey looked for references to flowers and herbs in a library edition of Shakespeare’s Complete Plays and Sonnets while Evelyn dug through a weathered copy of Hooper’s Guide to Gardening to learn what woodbine (honeysuckle), oxlips (primrose) and dewberries (blackberries) were. Next Evelyn sketched a diagram of grass, flowerbeds, bench, statue and vegetable garden.

With guidance from the local nursery, she and Richard built flowerbeds around the perimeter of the yard. The new vegetable garden, wrapping around the edge of the garage, would be twice as big as the original. Next came a three-tiered bed that sloped down the southern wall. At the top, they planted honeysuckle and jasmine. In the middle, primrose. At the bottom would be the herb garden. The back wall didn’t need much work. The cypress trees, like the ones in the Portland garden, were a natural backdrop to the full-grown rose bushes they planted—vintage, antique, crossbreeds and thoroughbreds. Janey drew handmade signs for each bush, which were replaced six months later by embossed metal ones that Evelyn had ordered.

In the fall, Evelyn and Janey buried bulbs in the soil next to the back porch steps and planted purplish-pink and yellow-blue pansies (‘love-in-idleness,’ Shakespeare called them) as groundcover. In the spring, the tulips and daffodils would burst into a ribbon of color.

A year after they began, they installed the final touch: Shakespeare’s corner. Richard cleared the ground and lifted the bust onto the concrete stand he had poured. Around Shakespeare, the heather bloomed into brilliant pink flowers from July to September. Next to him, they placed a wooden bench with iron scrollwork.

At first, Evelyn sat on the bench only to rest while Janey watered the roses or weeded the vegetables. When the days grew longer, Evelyn sat outside after dinner and tried to read Shakespeare’s plays. It was so laborious, one finger on the line of text, another on the footnotes, that Evelyn could read only a few pages each night. Gradually, though, the words began to fall into her. Evelyn found herself retreating to the garden at odd times of the day and night. When no one was looking, Evelyn would rest her hand on Shakespeare’s head, feeling a connection to him, as if he were trying to tell her something. It wasn’t until later that she associated the temperature of his head with the coming weather.

Janey and Evelyn spent hours in the garden on weekends, planting and pruning, cleaning up or planning for the next season. But when Janey began her junior year in high school, she abandoned the garden. After college, she roamed through Europe and Asia, coming home only long enough to save up for her next trip. Now, in her late thirties, she was living in Paris. Occasionally, Evelyn sent her seed packets.

“How’s your garden?” Evelyn asked now and then.

“It’s coming along,” was all Janey would ever say.

~

The morning after Shakespeare spoke, rain drips off the broken gutter and wakes Evelyn. She should have replaced the gutter when she felt Shakespeare’s head but she hates those kind of chores. There is also a broken doorknob to fix and two light bulbs to replace. Those used to be Richard’s responsibilities.

At seven, the clock chimes in the living room and Richard begins to stir. His hot body is too close; Evelyn throws off the covers. Using his right arm, Richard lifts his left leg, shifts closer to Evelyn and rests again.

The stroke happened more than a year ago, just after Richard retired. They were in the kitchen one Sunday when he dropped the cereal bowl he was carrying to the table. Evelyn reached for a dishtowel without looking up from the newspaper until Richard groaned, crumpling into her as she rose from the table.

Of those first six months, Evelyn remembers only the phone ringing and the roses looking restless. She went into the garden just once a day, too nervous to leave Richard’s side for long. His speech gradually improved and Evelyn helped him learn to dress, eat and speak again, almost, but not quite, like he used to. His face had changed, too. The left side drooped slightly lower than the right; the corner of his mouth permanently tugged into a faint grimace. The stroke itself hadn’t hurt, he told Evelyn once. Only living with it was painful.

Through it all, Evelyn woke up each morning and looked out the bedroom window at the garden below. Despite her meager care, it did not wither. But Richard grew tired of struggling up the stairs, so they moved from the bedroom with its handmade bed and view of the garden into the room behind the kitchen, which looked onto the driveway. They crammed into a narrower bed, touching hip to toe all night long. Evelyn had not slept well since.

Janey came home only once since Richard’s stroke, a languid weekend where she acted as if nothing had happened. During the day, she sat with Richard on the porch playing chess and once took him to a Trailblazers’ game. In the evenings, she helped Evelyn trim the honeysuckle but Evelyn saw that her thoughts were elsewhere. Janey chatted about life in Paris, hardly paying attention to the shears in her hand or the smell of winter around them. Evelyn waited patiently, breathing in the aroma of pine needles and fireplaces, but in four days Janey never once asked Evelyn how she was doing.

~

When the clock strikes eight, Evelyn sits up in bed.

“Are you going to go?” Richard whispers.

Evelyn hesitates, surprised that his voice is so clear, almost like before.

“Yes,” she says. “Janey is coming to stay with you. You’ll be fine.”

“Janey’s coming today?”

“No.” It all comes out in a rush. “When I go to London. I was able to get the package for his birthday celebration. The royal garden will be in full bloom.”

“Oh…you’re going to go.”

“That’s what you asked, isn’t it?”

He is quiet for a few seconds and then pulls himself up on one side. His cheek is creased from the pillowcase. His green eyes search her face. “I meant going to the store…for the gutter,” he says. “I didn’t know you made up your mind. We were supposed to talk about it.” He collapses, breathless, back against the pillows.

“I need to go…I’m going.” Evelyn tries to slow her own speech.

“If you just wait a few more months,” he says, “maybe I can go with you.”

“His birthday’s in April.” Evelyn speaks softly, edging out of the bed. She wonders if Janey really could take care of the roses.

“It’s that important to you?” Richard’s voice cracks. “You want to go without me?”

“It’s only once a year.”

“Maybe I’ll come. Why not? I’ll try…” He hoists himself up and swings his legs over the side of the bed. “I’ll fix the gutter.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, sweetheart. You never wanted to go before.” She touches his shoulder. “I’ll do it this afternoon,” she says. “I promised, right?”

“Remember when you tried to fix the screen door and nailed it shut instead? I’ll take care of it. All of it.”

“It’ll just be a couple weeks. Ten days.”

“We’ll see. Okay. Just…we’ll see.”

Evelyn crosses the room to the window and parts the curtain. The car sits in the driveway, its fender dented from an accident two years ago. She hears Richard behind her pulling on his robe with great effort. She is used to his gruff, throaty sounds as he struggles with what used to be a simple task. She doesn’t move to help him.

~

At eleven-thirty, there is a break in the rain. It is already the middle of March, almost too late to plant for spring, so Evelyn must hurry. She needs to finish the roses and plant something in the bottom herb bed. She doesn’t want Janey to do anything but water.

In the garden, Evelyn stands before Shakespeare, wondering whether to plant rosemary or wild thyme. Rosemary, the footnotes tell her, is a symbol of remembrance at weddings and funerals. It would hold up best under the cool weather but is prone to grow wildly, leaving its prickly stalks rough and useless. Thyme is more appealing but delicate and won’t last more than a few weeks. Evelyn can’t resist feeling rosemary is too serious for spring. Because of Ophelia, Evelyn associates it with winter and endings. She settles on the thyme as Shakespeare says quietly, “Yes.” Evelyn turns away from his voice.

In front of the rose bushes, Evelyn rakes the pruning into a pile. This takes longer than expected and she doesn’t leave for the hardware store until after lunch, having convinced Richard, she thinks, to rest on the couch. Evelyn watches him for a few minutes before she leaves. His eyes are closed and his body moves slightly under the blanket.

On the slick roads, Evelyn drives cautiously, thinking of Shakespeare’s voice. It was low and melodious, and now blurs into her own voice as she repeats “yes” to herself while she drives. The man at the hardware store helps her choose a replacement gutter. With all her questions about how to install it, she is gone for more than an hour. Finally she is back in the car and thinking of A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, which she is reading again. More than once she has fallen asleep thinking of the flowers in the book and the flowers in her garden. How she has brought them to life. Sometimes, just as she is drifting off, Evelyn hears Shakespeare call out her name in a sharp voice, like fingers snapping.

As Evelyn pulls into the driveway, she sees Richard lying on the porch. He is on his back, his arms reaching out as if swimming backstroke. The front door stands open, stopped by one of his flimsy slippers. A ladder hangs halfway off the porch crushing the hydrangeas below. Evelyn screams and runs past the ladder, up the stairs. She kneels next to Richard, pressing her face to his. She tries to feel his breath but knows she is too late.

“I said I would take care of it,” she says. She repeats this louder, again and again, until she is screaming. “If you’d just waited,” she weeps into his hair.

She collapses on Richard’s chest, his red flannel shirt soft on her face. He loves to be warm, she thinks, always in a flannel shirt or sweatpants. She wants to get a blanket, something, but can’t leave him. The wind has picked up, blowing the rain sideways. A small lake has formed on the walkway where it dips slightly. One of those things Richard had planned to fix.

The car door is still open, the sensor beeping into the gray day. Mr. Keegan is next to her. Evelyn gazes at Richard’s face. The muscles have gone slack and she is overcome with relief that the two sides of his face are symmetrical again.

When she returns from the hospital, Evelyn wanders alone through the house. The lunch dishes are washed and put away. The magazines, playing cards, and lidless pens are gone from the kitchen counter and a faint smell of ammonia hangs in the air. Richard had done it all. Even the tumbleweeds of dust on the floors are gone. Clean laundry is folded in a basket on the couch. Evelyn moves the basket to the floor and lies down. Rain drips off the gutter, the phone rings and Shakespeare calls to her from the garden. Evelyn pulls a cushion over her ears.

~

Three weeks after the funeral, Evelyn goes back into the garden. Underfoot, the grass needs to be cut; the dewy blades tickle through her thin sandals. The empty herb bed nags at her (rosemary or thyme?). The heather, bold and incessant, has taken over Shakespeare’s corner. Evelyn hesitates, suddenly weary, when she sees the stone bust.

Janey has come and gone. She arrived the day before the funeral and busied herself around the house, rummaging through Richard’s desk and bureau drawers. Organizing, sorting, boxing up, filling the house with activity. She hired men to fixed the gutter and smooth out the walkway. More than once, she tried to coax Evelyn into the garden.

“The roses need you,” she said.

Evelyn could only sit on the couch with a Travel and Leisure open in her lap, listening for Richard.

Maggie came too, bringing a new ticket for London.

“You missed his birthday,” she said, “but you should still go. It’ll be good for you.”

Evelyn relented. Only the garden was holding her back.

Now kneeling in front of the roses as the sun disappears, Evelyn dips a toothbrush into the bucket of soapy water and begins to clean the signs: Pretty Jessica, Wise Portia, Lordly Oberon. She has ignored them for so long they are almost illegible. While cleaning Tragic Juliet, a tall bush with pale yellow roses and thumbnail-sized thorns, Evelyn feels sudden distaste.

It is so much work, every year, the same weeding and planting. There has never been a moment where Evelyn could say, “It is finished.” And it will always be this way. She sits back and lets her gaze unfocus across the flowers so that the colors blur together.

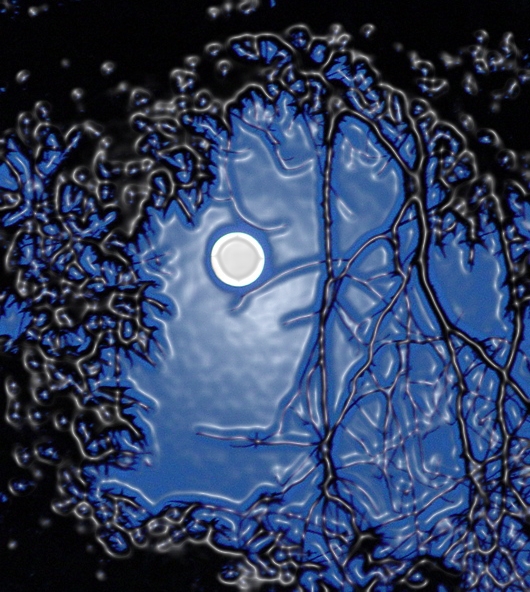

When she has finished cleaning the signs, the clouds have parted to reveal a full moon. Evelyn rests on the bench, kneading the knots from her fingers. She opens her notebook and begins to write instructions. “For whom?” Shakespeare asks but Evelyn ignores him. She charts what grows best where, how often to water and when to prune, surprised at how much she knows from memory.

As the cool night creeps up her legs, she puts down the notebook and tries to imagine London—the museums, the gardens, anything—but cannot turn that corner in her mind.

Jen McConnell is a native of Southern California who later moved to San Francisco where she began her writing life. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Goddard College. She has published stories in Bacopa Literary Magazine, SNReview, Clackamas Literary Review, WordRiot, UC Santa Barbara’s Spectrum, and the forthcoming Sports Anthology from MainStreetRag. After living on both coasts for most of her life, she currently makes her home on the Lake Erie shoreline. She supports her writing habit by working in non-profit marketing and communications. www.jenmcconnell.com

Read an interview with Jen here.