Mary Akers: Hi, Helen. Thanks for agreeing to speak with me about your writing process. One of the things that struck me right away in your marvelous short story “Mermaid Rock” was your use of sensory details. I love it when a story takes me there in terms of touch, taste, sounds, smells, and of course /images. You do this so well. Is this a conscious act of yours as you write? Or does it come naturally out of how you interact with your world?

Helen Branch: The initial idea for the story came out of a writing workshop I attended. The workshop energized my writing and as a result I started a word sketchbook. I wrote what came to mind, and for the story that became “Mermaid Rock” I had an image of a woman backing down the steps of a dock into a lake. I thought, how does that feel and how do I communicate it? It’s a common enough experience. We’ve all braced ourselves to go into the cold water. We anticipate the feeling, but it’s still a shock to feel the water move up your legs. I tried to capture the experience by breaking down all the sensory details. Then, my description sat in my sketchbook for about six months. When I found it again, I wondered, who is the woman backing down the steps, and why is she there at that particular moment?

MA: Wonderful. What a great way into a story. And it strikes me that the structure of your story is very unusual. It is definitely not a linear story, but I think it works quite well to get at Adele’s memories and her thoughts. Could you say a little bit about why you chose to structure it the way you did? And how much do you think a story’s structure influences the reader’s experience of the story?

HB: I couldn’t really use a conventional, linear structure with this story. Except for the ending, when she goes for a swim, Adele’s action is recalling events from her past. Of course, the act of remembering can be hard work. I tried to imitate that dynamic, and build tension as her memories culminate in the realization that her marriage failed her. When we remember the past we try to make sense of it and find the pattern. With Adele, I wanted to present a character that was reviewing her past, and her relationship, and coming to terms. And, I wanted the story to feel immediate and intimate and to mimic how we replay the past.

MA: When we were working together on revising the ending of your piece, we talked about the final image the reader is left with and the importance of “resonance,” by which I mean something like a tuning fork that once struck keeps on reverberating. I felt like you did a wonderful job with that in the revision, especially invoking the ripples on the water moving outward from her perch on the rock. How do you find your endings? Do you plan them out and then write toward them? Or forge ahead and find the ending in the writing?

HB: Endings are tricky. In an ideal world an ending would appear like a rabbit pulled out of a hat, but, instead, I’m frequently chasing it around the room. My first draft is just a narrative outline complete with where I think I’ll end. Then, the real writing begins. I try things on. I cut and paste. I reorder events, change names, add and delete characters. Sometimes I am surprised where the writing takes me. I hope, though, that the ending is an organic result of the story’s action. I want the reader to feel that, of course, this is how the story should end. Not that the ending was predictable, but just right, appropriate. I want to understand the ending too. I hate it when I am captivated by a story until the very end, and then left wondering, what just happened? And, of course, it’s always great to have an extra set of eyes look it over.

MA: Water plays an important role in myths, in our belief systems, even in the practice of faith. It’s cleansing, rejuvenating, life-sustaining and always changing but always staying the same. It can also drown us. How important was the lake to Adele’s transformation? How important was it to you as the writer, in accomplishing what you wanted to in the story?

HB: Water is central to the story. I use the characters’ interaction with the lake to reveal key aspects of their personality. The first time Tim sees the lake he strips off his clothes and jumps in. Adele is, at first, passive and sits high on the cabin’s deck watching the water. The reader knows she has a relationship with the lake. She learned to swim there and the rock jutting out of the water is ‘hers’. And the water here does perform an important, almost baptismal, function. The act of taking a midnight swim reunites the split Adele; the woman who recognizes the failure of her marriage and the woman who accepts the essential right to be herself.

When I was thinking about your question, I realized that water also plays a critical role in the novel I’m writing. The novel, “The Pebble Collection,” is about a woman who finds mason jars filled with pebbles in her aunt’s pantry. The pebbles were taken from a river on the property and they have a magical effect on the person handling them, allowing the person to believe in what they most desire. But, the river wants the pebbles returned. So, in this case, in the novel, water is a malevolent force. Like you said, water can both heal and hurt.

MA: Your novel sounds fascinating.

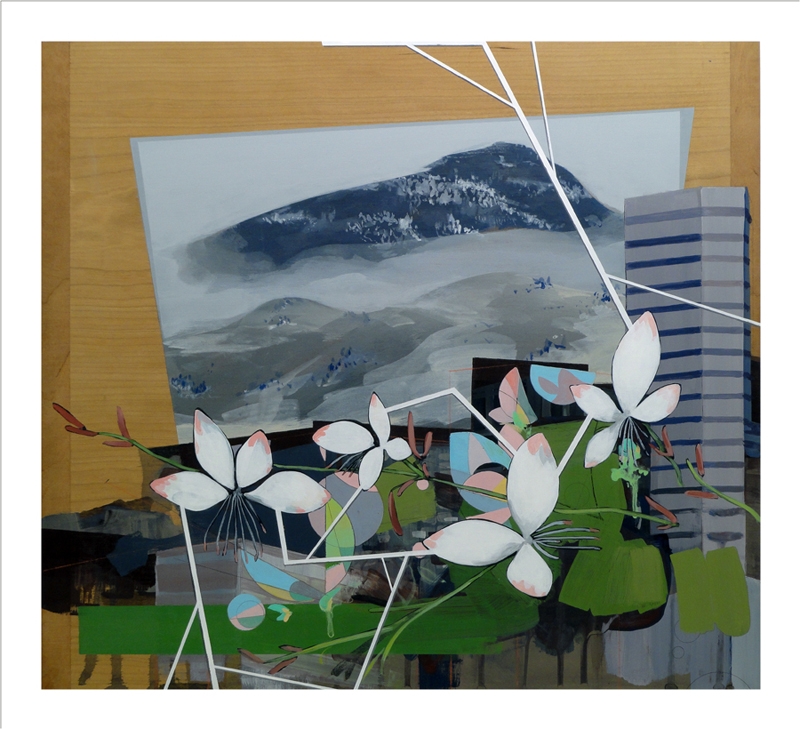

Our guest illustrator, Kristin Beeler, designed a unique piece of artwork for each story, poem, or essay. It’s a great gift to have an artist adopt each issue. To me, it brings the written work to life in new and exciting ways. The first image that she submitted for your story felt menacing to me, with the figure of a man in shadow, over a woman on the ground. It was interesting, but since we had revised the ending to be more hopeful, I went back to Kristin and asked if she wouldn’t mind changing the image. She did, and I was very intrigued by the one she came up with. What did you think of it? How would you describe it as relating to your essay?

HB: When I was ten or eleven I spent several weeks at a cabin on a lake like the one I describe in the story. There were seats hanging from chains under the porch roof and cushions made out of a course fabric like the webbing on a lawn chair. The cushions had a green plaid design. When I saw the picture Kristin had taken, I had a flash of recognition. I thought of those cushions. Of course, when I looked more closely I saw that it was parallel lines of rail road tracks. Good photography can do that. Like Edward Weston’s “Pepper #30”, it can represent more than just the literal image. The photograph ties in with the memory Adele has when she and Tim hike out to the train tracks. But the image with its repeating pattern of parallel lines is suggestive too of the patterns in her life that Adele is reviewing.

MA: I love that! How fabulous that your own experiences made it exactly what you wanted it to be on first viewing. Just like good writing can conform to the reader’s needs. Which leads us to my favorite question of all: what does “recovery” mean to you?

HB: I think we humans are fundamentally hardwired to tell ourselves and others stories. We are always trying to put ourselves into a larger context. We are finding patterns, revising, projecting where the storyline will go. And, we can get caught up in the wrong story. I believe that recovery requires us to step aside, to consider the story we’re telling. And, then rewrite it. Sounds simple, right? Of course, it’s not, but recovery lies in the process of rewriting. That’s why I was so excited to be published in r.kv.r.y. I thought “Mermaid Rock” fit with a vision of reclaiming, or recovering one’s story.

MA: Wonderful, Helen. We’re excited to have you in r.kv.r.y., too. And thanks so much for the discussion. It’s been great.