Way out in the middle of the open water about as far from land as one can get lurks the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. It’s thought to have started in the late 70’s or early 80’s; our globalized, mechanized, consumerized societies here in the US and in Asia teach us to toss away our trash with little thought to where it goes, assuming that once it’s out of our hands, it’s gone. But our world is really a closed loop feedback system. Nature has been secretly storing all our thrown away garbage, mostly plastics, in a peacefully austere location in the middle of the ocean where the winds blow both together and at cross breezes, creating a trapped area of calm in the center of all the circulating currents. A no-man’s-land where our trash is piling up, breaking down, overflowing and densifying at the same time.

Our problems pile up, too.

Childhood traumas real or imagined, adolescent hurts never soothed, adult needs and wants unmet, gaping holes unfilled, hungers never fed, pressurized obsessions never released, broken things unfixed.

Itches desperately unscratched.

One of the most interesting features of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is that much of it is unseen. While there’s more than enough visible trash to impress anyone who cares to look, though we usually don’t, most of the plastic has degraded and dispersed, so the water around the Garbage Patch looks clear but is actually infused with plastic particles. This soupy plastic water poisons its way up the food chain, getting into the unsuspecting plankton which get eaten by small, unsuspecting fish, which get eaten by bigger unsuspecting fish, until it reaches unsuspecting humans who should really know enough to be suspicious.

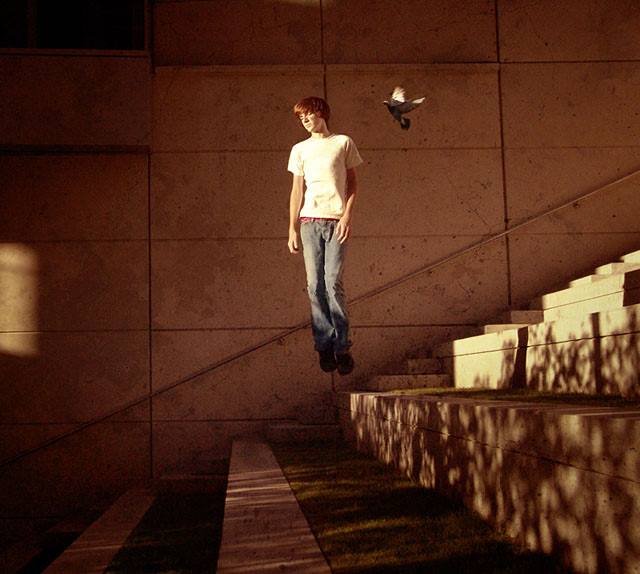

The whirlpooling repository of our garbage is also out of sight but definitely not out of mind. Our problems slowly infiltrate ourselves until the self isn’t the same self it had once been, the cancer starting from the outside and working its way inside, hiding in plain sight, going from outside us to inside us until it’s become … us, us transformed, transfigured, mutated, like the plankton that don’t, can’t, know any better. Like a mugging victim who discovers later that the whistle, the mace, the handgun, the powerlifting routine, the karate lessons, the cash in the shoe, the bars on the windows and the debarked attack dog have all blended into seamless, perfectly reasonable seeming parts of their lives.

Despite its appearance, hitting a big, obvious piece of pinpointable plastic like a bottle or a wrapper is relatively rare in the pervasive plastic soup of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Hopefully most of us have had only a limited amount of big, obvious trouble in our lives like a sexual assault, a car wreck, the untimely death of a loved one or cancer; something which changes our lives for the worse in a pinpointable singularity.

We’ve got the thickening plastic soup, instead.

The overdue bills in various shades of yellow and pink left sitting on the kitchen table, the fight with the wife that ended with grim mischievous satisfaction taken in her tears, the cold food delivered late which elicited a nasty call to the manager, the coworker who takes another donut even though he’s already consumed two and we haven’t had any, the phantom electrical problems in our cars, the leaky window we rattle until it cracks, the pushy ethnic neighbors who play their music too loud until we start wondering if the other millions of people in their country are the same way … all slipping into the relatively calm stillness out at sea after the vortex of stress is over, forgotten but not gone, dispersed into the thickening soup and slowly poisoning everything up the higher-functioning ladder until we drink too much or hit the kids or shrug at the suffering of others or go on a Columbine-style rampage after things reach the point that our diffused plastic soup has congealed into someone else’s pinpointable plastic bottle or statue of liberty, like a gradually gathered snowball hurled across a parking lot at an unsuspecting classmate who ends up with frigid dirty snow melting down the back of his shirt.

Whether god or science created the ocean, it wasn’t meant as a repository for our waste; our minds, our limbic systems are designed to deal with occasional hungry tigers or enemy tribesmen on the plains of the savannah, not the petty inhumanities of life in an apartment measured in square feet, in airplane seats priced on the inches of personal space we can afford, in deciding whether to order off the dollar menu or to splurge on the supersized option and then throw away the wrappers which eventually make their way to the Garbage Patch.

Some people’s garbage dump is a dry, dusty desert where things petrify and fossilize, while others have a dank, soggy swamp where fungus takes hold and grows. Rats and roaches and germs thrive on our waste, as do cynicism and disgust and eventually hatred. Who knows what Ebola or ISIS are evolving, waiting for just the wrong time to achieve critical mass and explode.

Is there a solution? Happy moments remembered and savored, a visit to a shrink, a weekend at a hot springs spa with detoxifying mineral water and a deep tissue massage included in the package deal? Someone invented a membranous maw to catch microplastic particles; someone else started recycling them. We can apply the effort to turn ugly events into harsh lessons learned. But the trick is to invest that ounce of prevention now, before a pound of cure becomes necessary.

Alexander Jones has short fiction and poetry appearing in Akashic Books, Bastion Magazine, Crack the Spine and DASH, among other publications. His nonfiction was recently anthologized by 2Leaf Press and an essay he wrote won GoRail’s 2012 contest. He has a BA in English/ Creative Writing and is pursuing a second BA in History. He works as a metal fabricator and lives with his family in New Jersey.

“Garbage Patch” first appeared in the journal Prometheus Dreaming.