Blue and Green Music by Georgia O’Keeffe, circa 1919

Rain. Each drop a finger tap on the roof, gutters gurgling. When the sun reemerges, northern California will green up like a piece of bread in a damp bag. To replicate an island’s edge, I’ll sleep in my car beside the cold ocean north of San Francisco behind a curtain of wind.

1. A woman with an English degree, I taught school, roping young people like calves into the corral of literature to discuss the human condition. Coaxing them to think, write. But a good teacher labors all the time, without the space of hours an artist needs to walk the open fen of creative thought. My stories’ characters stayed stuck mutely in scenes, the next line of dialogue impatient to be transcribed.

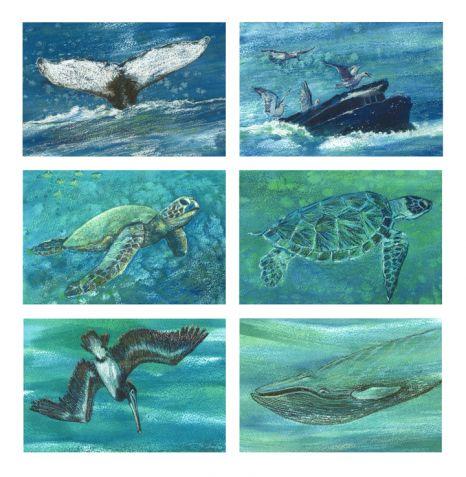

2. A photo of Georgia O’Keeffe’s classroom shows assignments hung on the wall, easels in rows. O’Keeffe taught school and painted until she could not sustain both, then chose painting. She tossed out, she said, everything she had learned to depict what she saw in a way that others might see anew. About flowers, shells, rocks and bones, she wrote, “I have used these things to say what is to me the wideness and wonder of the world as I live in it.”

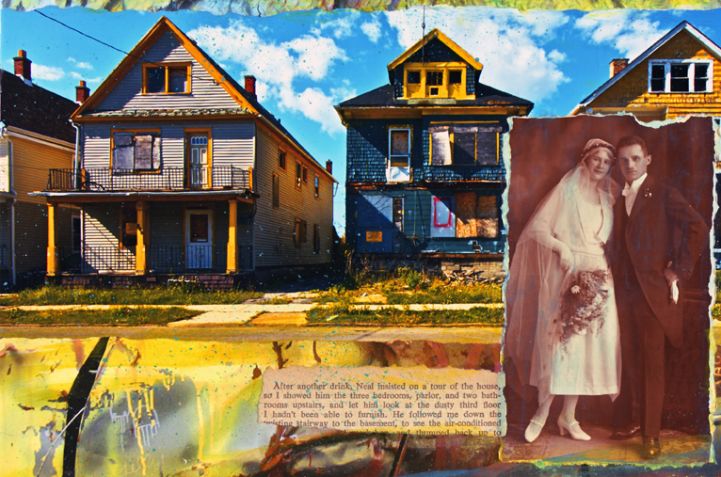

3. On colorful walls and in plexiglass cases at Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM), collages, paintings, and sculptures of self-taught artists reveal the depth of the well of creative enthusiasm: a ship glued from popsicle sticks; tiny scenes of prison life stitched from embroidery thread. AVAM proclaims: “Visionary art begins by listening to the inner voices of the soul, and often may not even be thought of as ‘art’ by its creator.”

4. At the men’s maximum-security prison near my home, the incantatory power of sound erases snow fences of race and gender. The inmates and I share each others’ poems and those of favorites, like Mary Oliver: “maybe just looking and listening/is the real work./Maybe the world, without us,/is the real poem.”

5. Artists’ work holds a heart before we know their biographies. When I fell into Jean Toomer’s “I Sit in My Room” I assumed the poet, like me, was a white woman. I hope he, whose father was born into slavery, forgives my laughable error. The poem whispers to any soul seeking to understand through a pen.

I sit in my room.

The thick adobe walls

Are transparent to mountains,

The mountains move in;

I sit among mountains.

I, who am no more,

Having lost myself to let the world in,

This world of black and bronze mesas

Canyoned by rivers from the higher hills.

I am the hills,

I am the mountains and the dark trees thereon;

I am the storm,

I am the day and all revealed,

Blue without boundary,

Bright without limit

Selfless at this entrance to the universe.

6. Through Yale University’s Room 26 Cabinet of Curiosities, you can view online two pages from Toomer’s journals. The simple notebook with lined pages resembles the kind the inmates and I use, purchased for a dollar or less. People are logging thoughts, each phrase a beam in a cathedral never to be completed.

7. With journals as portable studios, we make things and make up things. We strive to make up to the world for our limits, each new creation–poem or painting–another hat tossed into the ring of the attempt to understand the depth and breadth of the human condition.

8. By studying what happens when the sound of a jet disrupts their chorus, biologists learned that the songs of spade foot frogs form a musical camouflage that protects them from predators.

9. Each person’s poem or picture enters a biophony of interrelated soundscape across time and space, like Yeats’ song of Innisfree: “And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,/Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;/There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,/And evening full of the linnet’s wings.”

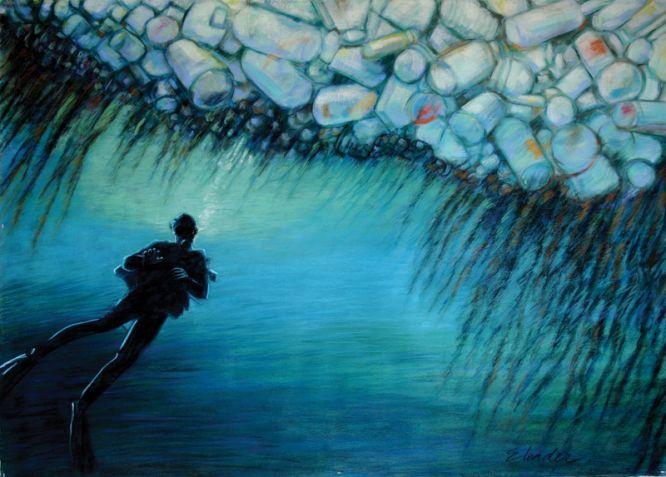

10. Art is our ant farm, our honeycomb, labyrinth, the anthology of infinite pages; each poem is a rain drop on its way to an ocean.

Alexa Mergen edits the blogs Day Poems and Yoga Stanza. Her poem “Distance,” published in Solo Novo, was a clmp Taste Test selection. Alexa’s most recent chapbook is Three Weeks Before Summer; and a full-length poetry collection is forthcoming from Salmon in 2015. For a full list of published essays, poems and short stories, please visit alexamergen.com.

Read an interview with Alexa here.