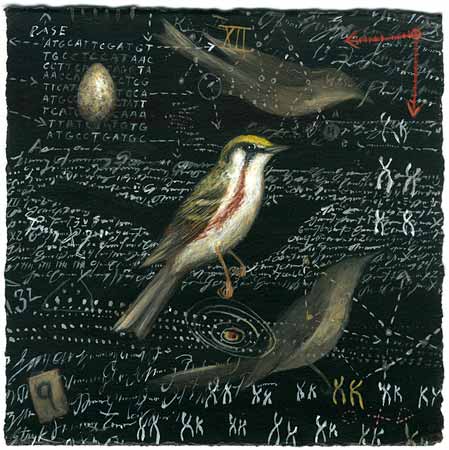

“Weaving Light” by Suzanne Stryk 2011

From between her legs something shot past, riding on a rush of blood and pale yellow fluid. When the flow ended, it was flaccid, inert; only the current had given it life. The nurse wrapped it up, took it away so fast I had to follow and ask, “What the hell was that?”

I was young, working alone—my resident, at his lover’s house, had left orders not to be disturbed. The nurse was an older woman of great girth and nimble poise. The patient was older too, older than me by a decade. Unlike so many in our hospital, she wanted the baby floating still and silent inside. You could when a woman wanted a child and knew hers was lost. You could tell by the ragged way she breathed, the way she gave in to the pain.

I was glad my patient wasn’t roomed with women whose babies were alive inside them, women with monitors strapped on tense bellies, clucking attendants coming to check printout strips or bags of oxytocin dripping slowly. Not always in our charity hospital, but often enough, those lucky mothers had men with them, husbands who wiped their brows, held their hands, and sweated as much as they did when it was time to check how much they had opened up.

This father was staying away or perhaps he didn’t know she had come in four months early. Perhaps he could sniff disaster from miles away. Maybe he didn’t care. We put his absence out of our minds; with her to care for there was scant time to fret about him.

It was only midnight and already seven in labor—three of them less than sixteen years old. I hadn’t yet gone to examine what she’d delivered but I had seen enough to give the woman a shot, something strong to make her sleepy. Just enough but not too much—I wanted her awake before the end of shift so we, the nurse and I, could tell her.

The nurse returned. I told her about the sedative; she charted it in her notes. The woman’s slumbering made the nurse nod, made a small smile crease the burnt-butter smoothness of her face. She had me help change the linens, remove the soiled pads, tuck the blanket under the woman’s chin and pull the side-rails of the stretcher up.

The nurse was mopping the floor when I left to check on the other patients. Everyone was doing fine, even the pregnant children, though there was one who didn’t understand what was happening. Her own mother didn’t seem to think she was old enough to know.

There was a fresh pot of coffee and a box of candy at the nurses’ desk. I grabbed two cups, filled them and stuck a handful of chocolates in my pocket.

We met, as if by design, in the utility room, where bedpans were emptied and linens were hampered, and specimens waited in trays of blood for the pathology runner on his rounds.

“Where is it?” I asked in a whisper, handing over her coffee.

She shushed me though it was just us and a stink or two and sad yellow-green tiles. Glancing at the closed door, she unwrapped the crinkly blue plastic bundle that lay on the table. “This is why I didn’t want that poor child to see what came out of her.” The gauze underside of the pad stuck softly; she had to jiggle it slightly to avoid tearing what was underneath.

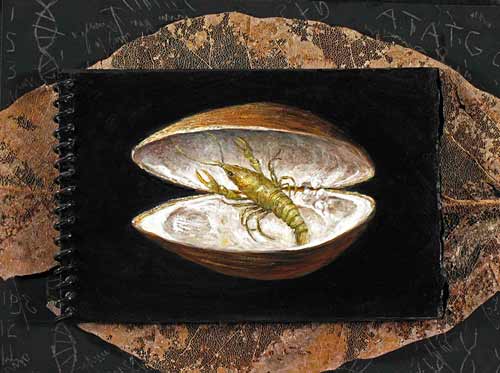

The nut-brown fetus rolled out onto the table. Four little perfect arms, four little perfect legs, and two eyes wide apart on one flattened head, frog-like atop the torso. The body had failed to separate, the head to fuse. A monster in miniature, a conjoined twin too distorted to live even in its mother’s womb.

I looked at the nurse and she looked at me, the warmth of us steaming up the little room. The hierarchy dissolved; we were no more doctor and nurse, experienced and raw, but comrades-in-arms, glad to have the company of the other. It was the middle of the night, when you feel most alone, like the last woman on earth.

“She can’t ever see that thing. You know that, don’t you, baby?” the nurse said to me. She didn’t have the power to make that happen. I did.

I nodded.

In the long gray hours of the morning the nurse called me back to the woman—drowsy but moving under her wraps. “Doctor, what was it?” she asked.

I drew in my breath. “A boy, born way too early, born dead.”

“He was my first.” She didn’t ask to see him, didn’t cry.

“You needn’t worry about him, honey,” said the nurse, stroking the woman’s hand. “We took him away, made sure he was comfortable. Made sure he was all right.”

“Thank Jesus,” our patient said. “The Lord must have been with him.” She closed her eyes, drifting off in a haze of morphine. I was called away for another delivery and then another. I knew the nurse checked on her, circling back as often as she could. She was discharged in the morning; I never saw her again.

For more than twenty years I’ve thought about that night and that nurse, now a decade dead. How she stirred a woman’s faith, cooled her brow with water. I thought about that most when I was pregnant, feeling faint fluttering and wondering about what was swimming inside me: A disc curling to cover a raw spinal cord? Two bright eyes migrating–as they should–toward the front of a child’s face? Limb-buds–ends flattening like seal flippers, tissue dissolving to expose ten little fingers?

And when clinging to faith was difficult and normal hard to envision, I found I had forgotten how to believe. I sat in my rocking chair, felt my baby growing and longed for my nurse to say everything was all right.

Even if it was a lie.

Judith Beck is a physician in California. At present working on a novel, her previous publications, in print and on the Web, have included honorable mention in Best American Essays for “Button Up Your Overcoat,” published in Prairie Schooner.