“Unfinished Business,” oil on canvas, Darwin Leon, 2010

Jake pulled into the driveway and saw Ruth sitting on the front porch steps, bundled in her parka, wool mittens, and a black stocking cap. Her arms cradling her legs, she looked like a child waiting on her father to arrive home from work. In the headlights, her eyes were radiant in the brisk chill of the coming dark. He cut the engine and scrambled out of the car. The snow crunched under his feet.

He placed his briefcase beside her and sat down on the step, careful to avoid the melting snow. She leaned her body into his and he put his arm around her. He couldn’t feel the heat of her body through the heavy fabric of their coats.

“You missed them. They built snowmen.”

In the neighbor’s backyard sat four snowmen in different shapes and sizes, each, he imagined, made to represent a member of the family. He concentrated on their features and was mildly shocked by the placement of the eyes, mouth, and nose on the smallest one. It looked like an expressionist painting, with everything slanted to one side. If it were his child’s he would have waited until the boy went inside and then corrected it.

“How long have you been out here?”

“An hour, who knows. After the appointment…I don’t know.”

He was amazed at the airy silence; shadows brave against the dying sunlight bounded around corners as the streetlights popped on. The search for the perfect excuse stirred in his hands keeping him warm. The snowman made him anxious, as though its imperfections would somehow ruin his explanation.

“I was sitting here trying to think of a way to hide it from you, but when those children came plowing out the door, I lost it.”

He stood then and looked down at his wife; her face veiled in his shadow; her eyes liquid; her cheeks wind burnt and chapped, and then she shivered.

“Ruth, I’m sorry. That couple showed up late and there was all that snow melting on the hardwood floors. I couldn’t just leave it that way.”

“It doesn’t matter. Forget it, okay?”

She stood, wrapping her arms around his waist. She looked up at him. A strand of hair came out from underneath her hat, resting over her eye.

“Dr. Lesko went over our test results again and there are just too many of those things. God I can’t even say the word.”

“Cysts?” he asked, his voice sounding too loud in the muted darkness.

“Yes. God, cysts.” She crossed her arms over her chest.

“If there was something I could do…”

“So you’re off the hook.”

“But, I’m still you’re guy, right?”

“Oh hell, you know what I’d love?” she said. “I’d love to wake up tomorrow and look out the window and see them gone.”

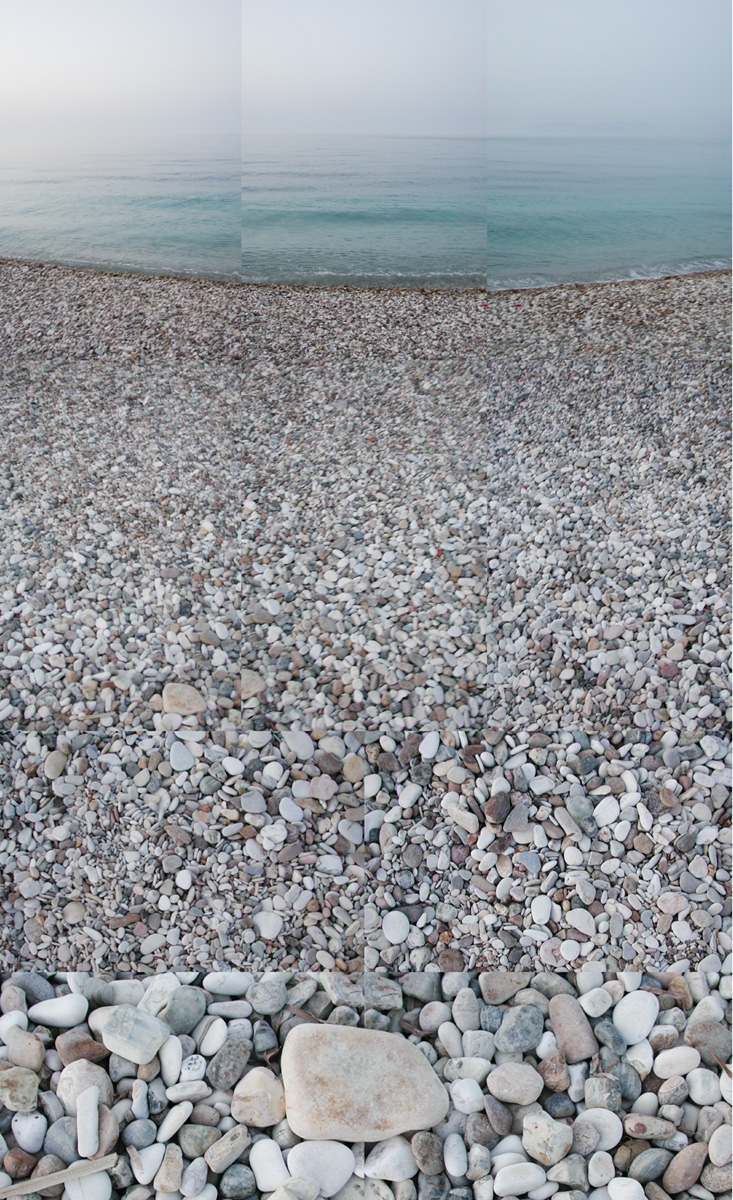

In front of him a vista of white decorated the neighborhood like a baker’s frosting: cars, roofs, yards, and scaly tree branches doused in confectioner’s sugar. Above and below him, sky and ground shimmered like tiny penlights.

“I could do that, I could.”

“God, I’m so…so utterly…Don’t I deserve to be angry?

“What if we had something else to concentrate on?” Jake asked.

“Not you, too. Don’t patronize me, not now.”

Staring down the street, he thought of all the parents putting their children to bed, giving them a quick kiss on the forehead, before heading off to their own rooms, where they’d cuddle together under the heavy covers. They’d fall to sleep knowing their children were safe and warm, happy to have another day in a happy life. Well that pissed him off, because he wanted to know just who had decided that they couldn’t have the same damn things.

“I can’t look at them anymore. It’s like they’re watching me,” she said.

“Go, then.” He softened his voice. “I’m right behind you. I just need to get something from the car.”

She sighed, her breath turning to fog then dissipating into the night. “Take your time. That’s all we have left.”

She clomped her shoes on the porch, creating watery footprints. After she closed the door, he watched her walk into the house, coat and shoes still on. The water from her shoes would hide in the carpet and later he would step in it, soaking his socks and freezing his toes, his circulation too slow to keep his feet warm. Every winter they went through the same thing, he’d ask her not to wear her shoes past the kitchen and she would claim to forget. Ten years of marriage and nothing had changed.

He dashed across the street, almost slipping, but regained his footing and stood in front of the two smaller snowmen. He raised his foot and kicked at the base. A chunk of snow collapsed to the ground and the midsection shuddered and canted to the left. He punched and pawed at the baby until his hands were cold, red, and raw with the crust of melting snow. A carrot, broken in half, lay at his feet near the squished Oreo that used to be its eye. He turned his back on the mess and walked away, knowing that his footprints would harden overnight, and that tomorrow when the neighbor stood on their porch they’d forget, for just a moment that nothing would change.

Tommy Dean works as a high school English teacher. A graduate of the Queens University of Charlotte MFA program, he has been previously published in Apollo’s Lyre, Pindeldyboz, Boston Literary Magazine, Blue Lake Review, and 5X5.