Image by Kristin Beeler

Adele sits on the wooden Adirondack chair, her elbows and hands resting on the paddle armrests.

The dense summer air makes it too hot to move. Gnats encircle her head. She keeps her eyes and lips closed against them, but they whine in her ears and enter her nose. She is stone, she thinks, although the sawn off edges of the chair are sharp against the skin of her thighs.

As a child, she had gone to the cabin with her mother and father. It was the only cabin on the lake, surrounded by the wild woods. She had brought books to read, curling in the cushions of the swing seats hanging in the wide front porch. The cushions were covered in green plaid material that had a plastic sheen and smelled of damp. It was a time in her life when she could read all afternoon and be dazed when someone called her name.

She had gone swimming in the lake. Parts were very deep. She would float in an inner tube, her arms hooked over the rubber, warming in the sun. The current would take her into ribbons of startlingly cold waters; she would tread to stay in pockets of warm. Near the dock the water was shallow. Adele could wade out twenty feet before she couldn’t touch bottom. Another fifty feet beyond was an unusual rock formation. Like an iceberg, most of the rock was submerged under water, but enough of it protruded out to create a mini-island in the lake. She had named it Mermaid Rock. The first time she really swam, she swam to Mermaid Rock. There was just room enough for her to climb out and bask in the sun.

After her marriage, she had brought Tim. When they drove in the first time she pointed out where to park, where pine needles dampened the ground and cleared off encroaching undergrowth. He had gotten out of the car, breathing in the air, looking over the cabin and its porch facing the water. She had been pleased watching him take it in. He’ll love it as much as I, she thought, thinking of him opening an unanticipated gift.

He had stripped off his shirt, stepped out of his sneakers and shorts and in bare feet had run down the path onto the dock. Don’t dive, she called after him. It’s too shallow.

The heat continues into the third day. She thinks I have made a mistake coming here. That night, she reads by the light of a gas lantern, and then bored, she carries her lantern up to bed. She peels off her t-shirt. Drowned gnats are pooled in the hollow between her breasts. She wipes them off and stepping out of her shorts, she lies down naked on top of her bed, and puts out the light. Her bed is in front of a screened window. She hears the awakening of the night as creatures move in the brush. There is no breeze.

One time they had hiked into the woods. Tim carried a backpack and in it Adele had packed some sandwiches and a thermos of iced tea. They ate their lunch in a small clearing, sitting on a fallen tree trunk. They saw a praying mantis clinging to a twig. Look how large it is, Adele said. Tim touched it, tried to catch it, but it fell into the grasses and they couldn’t find it again.

Adele lies in bed for some time listening to the woods. Inside herself she rustles and scratches, picking at things buried. Finally, she gets up and running her hand along the wall, goes down the stairs and outside. She leans against a round log post that supports the roof of the porch. It is cedar, tall and straight, its bark peeled off and the surface hard and smooth. She wraps her arms around it, places her cheek against the wood. It is cool. Where branches had been there are worn rounded knobs. One presses against her hip bone and hurts.

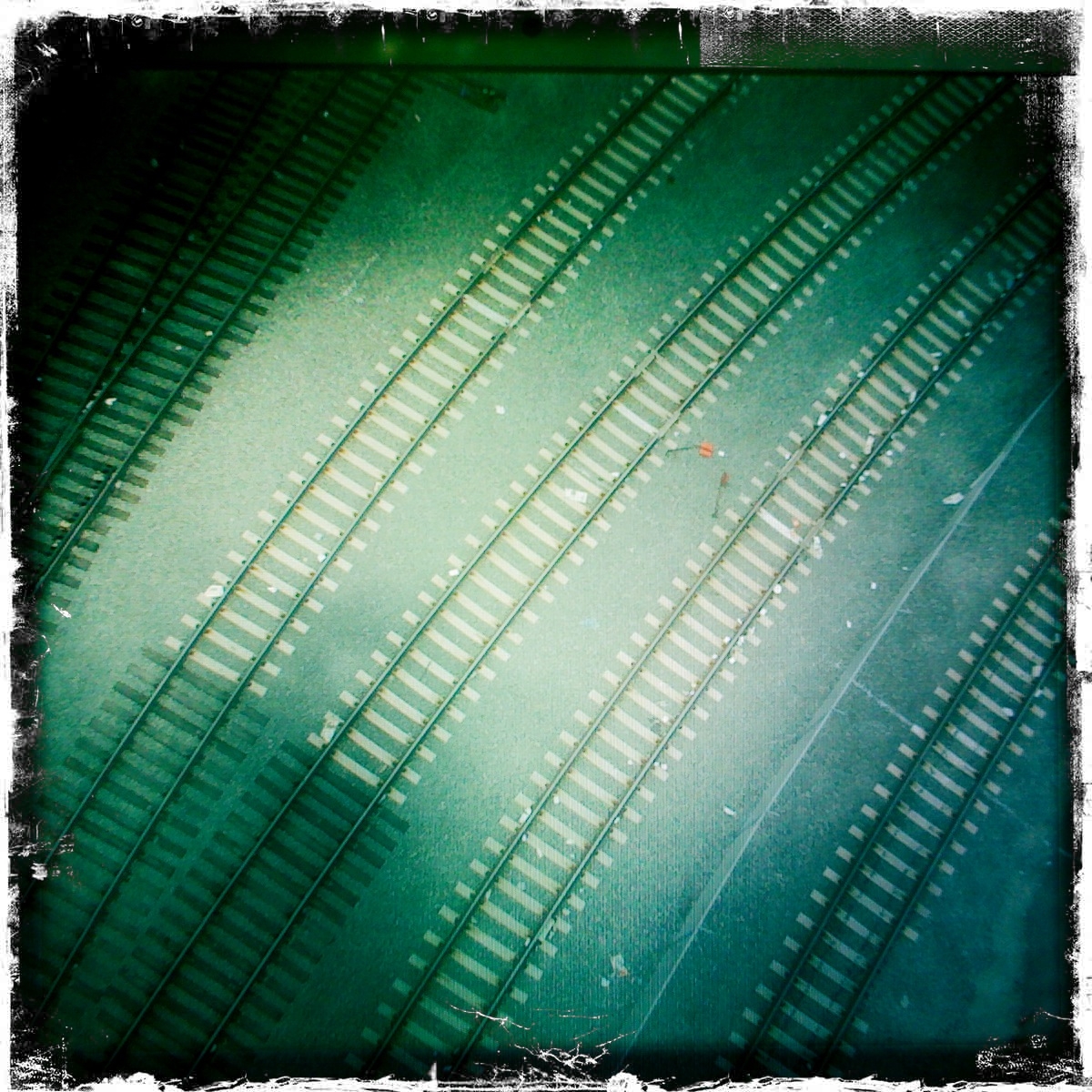

They had walked until they came to the railroad tracks. The ground on either side had been cleared of brush and the tracks themselves were on a long raised mound of earth. It was steep to climb to the top but Tim scrambled up and walked from beam to beam. Come on up he said.

There is no air to breathe, few stars. The full moon is larger than life, a cool imitation of the sun, casting shadows that slide in place. The light plays on the surface of the lake and, from where she stands, alone, she can see Mermaid Rock.

It’s a freight line, Adele had said. It’s still used. I counted one hundred and twenty one cars one time. Tim squatted down looking up the line where the rails disappeared into the distance. He sat on the middle of a tie and put a hand on each iron rail. I’ll feel it coming before I see it. And then he lay down, his arms outstretched. Come on up here, he said. It’s too steep, she said.

That was a sign, she thinks now.

Come on, let’s do it, Tim had said. Here on the rails. She said what? Are you kidding? Outside where anybody can see? The trains come through here all the time. It’s too dangerous.

Tim had laughed, teasing. It’s coming, he said. I feel it. Come up here now before you miss it.

Tim, she had called. Get down now. And Tim had laughed and said it’s coming, I can feel it.

Adele had looked down the line to each side, had climbed up a bit of the slope to see better and then she did see the train, a bright light on point. Tim, she said, please, but she backed down and moved beyond where sharp gravel had been poured to keep back the weeds. She could see Tim’s hands gripping the rails and now heard the train, the sound catching up. Then the train arrived roaring over the rails, deafening and sharp with friction. And, she couldn’t see Tim. He had disappeared.

Adele had sat by the side, watching the train cars go past. Car after car, minute after minute. He’s rolled to the other side, she thought. She brought her knees up to her chin, sitting like she sat when she was a little girl at the edge of the fire pit her father made, watching the flames and sparks twirl up into the air. When the last car went by, she climbed up the slope, looking for Tim, waiting to hear his laugh, laughing at her for her timidity, embracing her. But, Tim wasn’t there.

She had headed back to the cabin. How strange, how disorienting it was to walk back alone. She knew the path and kept to it, checking off the landmarks as she came to them. Could Tim find his way back without her? Should she call the police?

When she had gotten back to the cabin, Tim was swinging in the hanging chair under the roof of the porch. How did you get here ahead of me, she cried.

She thinks now, she will swim to Mermaid Rock.

The path down to the lake is steep. There are flat stone steps and a dirt path. She walks carefully, the sharp little pebbles biting into her feet. She reaches the dock. There is a ladder on the side of it so that you don’t have to pick your way over the slippery green muck near the shoreline. Turning around, she steps backwards and down.

Tim had gotten tired of her. She was a drag on him. They never did anything, he said.

The first brush with the water is a surprise. Her breath catches high in her throat. She pauses as the water laps around her ankle. She takes her next step down and the coolness twines itself around her shins. The next step brings her to the bottom. She stops there, feeling the sand and pebbles slip under her feet, the water rocking, and then settling as she stands.

The surface of the lake is unbroken until Mermaid Rock pushes through.

Adele wades out away from the dock. The lake bed yields to her with little whirlwinds of sand. The water raises cool up her legs, up her thighs. She holds her arms up, arced in front of her, above the surface of the water and still she goes deeper. The water’s edge laps over the curve of her hip, rising to below her navel. Adele holds her stomach in tightly as every pulse of the water reaches new skin. A flush of cool sensation ripples up her chest and radiates around her breasts drawing each nipple tight. Looking down, the moonlight is reflected. She is bisected now, two Adele’s. One is heavy, above the surface, clammy with the day’s sweat. The other glows softly, cool, her pubic hair curled densely with small seed pearls of air, little baubles that lift themselves and circling, float up.

She takes a breath and tilts forward, falling. The water catches her. Her arms shape a v for her head. She lifts her hips up, pushing her torso down under the water and forward, moving to Mermaid Rock. The cold, through her hair, down her neck, engulfing her is stunning. But, as quickly as she feels it, the shock is over. The water rushes against her ears, supporting her weight, but beyond that, the water has ceased to exist like the air she breathes.

It takes only a few short strokes and she is at her rock. She touches it with her hand. It is granite, hard and studded with quartz that glitters in the moonlight. She climbs up it and the lake sends out ripples to the shore that echo and then grow quiet. She lies on her back, her feet still under water, her spine following the gentle upward curve. Adele shimmers like Mermaid Rock in the night.

Helen Branch is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University. She holds a BA in Political Science and a Masters in Industrial Relations and worked in Human Resources before resigning to raise her two sons. She currently volunteers at a domestic abuse agency.

Read our interview with Helen here.