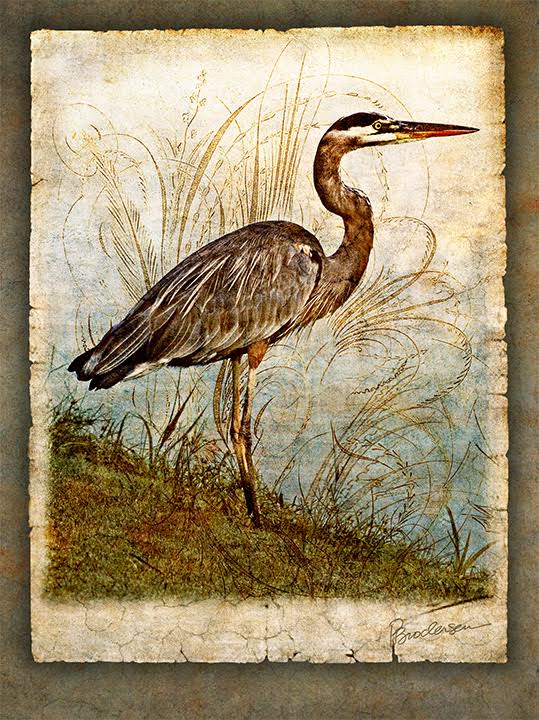

“Evening Light” Image (detail) by Pam Brodersen

A few months ago, a hole appeared in my bedroom. For the first few days, I mistook it for a balled black sock as I dressed for work in the grey mornings. I didn’t have to wake up that early, but I liked to. An early run does wonders when you’re stuck in an office all day.

On laundry day, I reached with my toes to grab the stray sock and instead a cool whisper of air tickled the hairs of my big toe knuckle. I pulled my foot back with a shiver and looked closer. It was smaller than a baseball and too deep a black for fabric—a drop of pure night sky pooled upon my floor.

There’d been no breeze, I assured myself, and holes didn’t appear for no reason. On all fours, I looked into the hole. It seemed deep, possibly bottomless. The edge showed a cross-section of floorboards, as if cut and carefully sanded. Under them was . . . nothing. Nothing, where there should have been floor space and support beams. Or at least my downstairs neighbors. I reached out, slowly.

This breeze felt colder than it should. Memories floated up: as a boy, cracking open the freezer on hot nights, standing on my toes, pushing my neck toward the chilled air—cool, dark, and lonely. I pictured my floor floating over nothing—in a great vacuum. I stopped. I’m not afraid of heights, but something about that picture—the vast emptiness, and me floating somewhere in it, left me nauseated.

I made a deal: if the hole was still there when I opened my eyes, I would stop calling myself crazy.

It was still there. I wasn’t crazy. Is that something you could decide? Like not letting the rain bother you by deliberately walking slowly?

The air felt even colder as I reached my arm into the hole. Once my arm was fully extended, my fingers danced for contact. I tried to stretch the space between my joints. I felt nothing but pressure, like I’d reached into a deep sea.

Well, maybe I wasn’t crazy, but that damn hole sure was. I debated calling the super, but I couldn’t guess what he’d think. Something deep within rose up at the thought. I couldn’t tell him. He’d blame me, say I was vandalizing the place. So, I did what I do. I ignored it.

*

A few days later, I stepped into it. A feeling of weightlessness ran up my spine, expectations upended. In that moment—during the inch and a half drop—I questioned. Would I keep falling? Had the floor had caved in? Had there ever even been a floor? These doubts, although faint, sprang up in the back of my mind as if I’d always been ready to question the basic laws of physics and that brief moment gave me a reason. And then my heel stoppered the hole. Painfully. The sharp edge scraped back skin. The distraction of pain dispelled the worries for a time.

But later, as I tried to sleep, doubts poked me awake. Then I dreamed of drifting through space on a tiny raft of floorboards—no air but somehow still alive. It became recurring. I’d have nowhere to go and nothing to do but count the stars and watch the occasional comet pass. Sometimes, it wasn’t so bad. But then I’d wake, gasping for air, as if the vacuum had finally closed in.

I tried to get back to my life. I woke early and ran. I ate and worked and drank and slept. More routine than I anticipated when I moved from Flyspeck, Ohio to Chicago. I had a few friends, at least—was part of a semi-regular crowd at the bar. The occasional date went well. Or they used to. Since the hole appeared, I’d been hesitant to invite anyone over.

*

I noticed a whistling sound a few weeks later. I blamed ringing ears, faulty electrical wires, static hums from the TV. I even pictured some far-off jackass playing with a dog whistle that I could barely hear. But I knew what it was. It sounded hollow. I ignored it. I tried to. The hole grew, and with it, the wind.

*

A few days later, I almost dropped a whole leg in. I’d gotten comfortable with my habit of stepping wide as I entered my closet, gaze aimed carefully away. But this time I reeled forward, pushing hard off the sharp edge and falling into my closet, landing painfully on one knee. My other foot dangled in the hole behind me; air rushed around my ankle. No longer the whisper I’d felt before, now a steady flow of crisp, dry air, as if it swirled over morning snow. I looked closely for the first time in weeks.

A watermelon could have rolled in with room to spare. I pulled my foot away and spun around to face it. With the hole so large, more light should have revealed its depths, but inside was the same deep blackness in every direction. Vastness. I stood and dressed as if nothing had changed, but was careful to jump over it on my way out.

*

A week later, I had the usual crew over for poker night. I was only close with Mark and Iris, but we needed more for poker and my place had the largest living room. I usually left my bedroom door open as a low-key invitation for Mallory, but that night I shut it and wished it had a lock.

The hole had grown so large it filled the closet doorway. I put a cardboard box over it. I tried to forget about it—easier said than done. Twice that week I’d found myself staring at it without realizing. But this was poker night—no room for the void.

The game was going fine. Seb had the lead, as usual, but I had a good start. Mark flamed out early, but was enjoying spicy wings in the kitchen. I was nursing my third beer and trying to stay calm. I had pocket kings. The flop came out with another. I was riding pretty. Iris and Blair stayed in, bets came out, and the pot grew. One of the biggest of the night. Everyone watched.

“What’s that howling sound?” Mark asked. “Is it storming?”

A cold fist gripped the base of my spine. I kept my eyes on the table. No big deal. I couldn’t relax my shoulders.

Iris raised an eyebrow. She’d had her hand on a large stack of chips, probably to call my bet. Instead, she sighed. “I fold. Nice try looking scared, but you exaggerated it.”

Seb made an oof at the hand—he wasn’t one to be distracted—but now Mallory and Mark both were looking out the window and cocking their heads. Yellow street lamps illuminated still trees and grey, week-old snow. No storm.

“Is there a window cracked?” asked Mallory.

My stomach churned. “Oh, yeah, in the bathroom,” I said, hoping poker had helped my bluff. “The heater’s in there, so it gets crazy hot.” I felt trapped in my clothes, hotter by the second.

No one got up to look. A few hands later, Mark went to the bathroom.

“Does that window even open?” he asked as he reemerged and stood by my bedroom door. “It’s louder over here.”

What if they saw? What if they fucking saw? They’d want to know: what it was, where it came from, how it happened. How could I explain? Maybe they’d laugh it off as an oddity. Tell me to fix it already. I told myself it wasn’t a big deal, that it would be easier to show it than describe it. But I couldn’t. Deep down, I knew I couldn’t.

“I think it’s coming from in here.” Mark tapped on my bedroom door.

Panicked, I said, “Oh shit, you know what, I forgot I left my humidifier on.” My mom had one. It always made weird noise.

“You use a humidifier?” Iris asked.

“Yeah. So what?”

They were looking at me. My neck felt wrapped by a thick, scratchy scarf.

Mark reached for the doorknob.

“Christ, Mark, leave it the fuck alone,” I said.

Seb and Blair exchanged looks that said, spaz. Assholes.

Mallory looked concerned, a little annoyed. Fickle.

Jayesh hid in the kitchen, avoiding the tension. Coward.

Iris looked offended.

Mark raised an eyebrow, still listening at the door.

“Poker,” I said, in a more relaxed tone. I could still be chill. “Let’s play, man.”

Mark listened for a few more seconds. He said, “It sounds weird,” but walked back to the table and sat.

My game fell apart after that. Seb won. But they left and I could breathe again.

I approached my bedroom door and cracked it open. The howling had grown. It was a wonder they hadn’t all heard and stormed in.

The cardboard was gone. The void must have swallowed it. A quarter of the room was missing—baseboards hung over empty air on both sides. Wind pulled at my clothes as if it might pull hard enough to unbalance me mid-stride.

I sat on my bed and stared into the void. I pulled the blankets close around me and shivered as I stared.

My alarm went off, startling me. I’d fallen asleep slumped against the wall. My neck didn’t want to straighten. I hit snooze, but didn’t. Instead, I sat on the edge of the bed and stared. I could run tomorrow. Something drew me into that void. It was cold, dark, and lonely. Captivating. I was late to work that day. Only by a minute.

I tried to get back into my routine, but failed. My morning runs, most of my sleep, my bar nights, they all fell away. The howling wind became a blizzard and loose objects started disappearing. I’d find myself awake, lying on the edge of the bed, staring toward the hole while the wind pulled at my blankets. I had to sleep with them curled underneath me to hold them. I could still see the void in the dim glow from my alarm clock—a darker shadow than the rest.

I started stumbling into work, late and red-eyed. I had a meeting with my project manager last week about coming to work hung over. She wouldn’t believe I wasn’t.

I saw Mark and Iris a few more times, but I avoided the group. Mark kept asking me what was wrong with me. Iris kept saying I looked stressed and patting my arm. We were supposed to play poker again yesterday, but I cancelled. Iris has been texting me a storm since. Mark sent a few angry texts, but gave up.

My phone vibrates in my hand. It’s Iris again. She sounds worried. I should say something. Tomorrow. I’ll text her tomorrow.

I look back into the void. It’s truly massive now. My bed’s the only thing left in the room save for my desk and chair, out of reach, in the other corner. I’ve been here all day, sitting on the edge of my bed. My feet hang off the side, chilled to the bone in the howling wind. My heels rest on what’s left of the hardwood floor. There’s only three or so inches left sticking out from under my bed, barely enough for me to stand.

It’s been growing. Soon, the entire floor will be gone. Will my bed slide in and fall away? Or will it be like the walls by my closet, floating on nothing like a raft on a sea of emptiness? I balance on the lip, calves against my bed. The wind tears the blanket from my grip and swirls it around the room until it catches my desk chair and pulls them both into the void. They fall away, further and further until the black envelops them. I raise my arms to feel the wind. It’s almost strong enough to lift me.

Ryan Stembridge recently graduated with an MFA in fiction from the University of Memphis. He enjoys magical realism and exploring experimental formats, as well as more traditional styles. Ryan’s poetry recently appeared in the Merrimack Review’s spring issue and he worked as an editor with The Pinch Journal for three years. Outside of writing, Ryan is a proud new father and sometimes sleeps.

![Missile Paradise by [Tanner, Ron]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51e4R9ml5tL.jpg)