In winter, the heat-rocks keep the dining room — the thermic core of my home I like to call it — several degrees warmer. Sometimes when I get blue, which happens more as the days go short, I cook up all the snake tank lights and lay down on the floor with my sunglasses on just to feel better; that’s why there’s no furniture in there anymore, because as everyone knows I am very, very tall.

So when Hot-cha, that’s what we call Jason White because that’s what he calls himself, comes by that Friday to get me, I’m laid out on the dining room floor trying to make my back feel better and trying to get a better feel for life.

“Yo, git-cho punk-ass up off dat floor, Stretch!” He jiggles the door handle as if he means to tear it off. “Don’t make me put some caps in this door, you long old piece of schnizzle.” I don’t think Hot-cha knows what he’s saying when he says a lot of the things he says, but I like the way he makes up words: poetry if not particularly poetic.

The bones in my back feel loose and good as I rise, the nubs of my slack spine giraffe-necking in graceful cooperation until the ax-chop through my left hip stumbles me. “C’mon then,” I say, opening the door with one hand and holding onto my left hip bone with the other. My hips, doctors say, flare out like an open baseball mitt and put too much pressure on my lower vertebrae. Hot-cha, meanwhile does his dance shuffle through the door, tugging at his parachute pants and his shirt and wobbling his head as if he’s making fun of

my limp, but that’s not true. That’s the way he’s taught himself to walk.

“Why doncha just get those hips removed so you’re not gimping around like my dead grandmamma? My sister, Janice, worked with this chick at Target that had her hips taken out, she couldn’t have no babies anymore, but so what, right? You ain’t looking to have no fifteen foot tall babies, is you?” He actually waits for me to answer. “Aw-rightden.”

On Fridays we go to Stiv and Lois’ Steakhouse on 41, and usually we meet Carlton there. Sometimes Carlton brings Alan, but only in the winters because Alan works the megafarm out near Dakin. Russell shows up sometimes too, when he doesn’t have a date, which almost never happens. I suppose a few others duck in enough to merit mention.

Hot-cha knows all the waitresses and both cooks and usually we can count on them holding the same table near the kitchen where I won’t draw so much attention. I don’t mind people staring after me, or asking me if I’m in the NBA, or even pointing, which is what the children mostly do. But what makes you think I don’t know what you all say when you lean into your table, head and eyes swiveled my way, and talk in whispers? I am taller than you are and my hearing is extra terrestrially acute. And I can smell things no other human being can smell – like fear. I might be tempted to tell you that I also obtained extra sensory peremptory powers, but know you’re inclined to be skeptical. Why, you’ve already glossed over the details about Hot-cha, thinking that you know the kind of person he is and the role he plays in this story. And if you’d seen me in person you’d have made similar assumptions about myself and what the kind of story I might tell, which is all right, that’s very a human thing to do, but you’d be dead wrong. Just like you were wrong in thinking I

misspoke when I said ‘peremptory’ instead of perceptive. The lesson here: Don’t ever equate tall with stupid.

Hot-cha’s car is a sedan, which is good for me because he also has independent seating that can go back and lay all the way down. Sometimes, because I lay so far back, I think it must look like a child with a very enormous head is riding in the back seat and I think again about what Hot-cha said about never having children and thank my lucky stars there’s still time, if the right woman comes along, though the idea of children seems more realistic — plausible, so to speak — than the ideal woman somehow and I remember a similar thought I had several hours ago which caused me to have a lie down in the thermic core.

Hot-cha’s car has license plates he paid $50 extra for to say “HOT CHA.” He buys lots of things that say Hot-cha. You could say that this is a hobby for Hot-cha, and one time, when I was at a truck stop outside of Omaha, I found a keychain that already said “Hot-cha!” on it and I bought it for him as a prize possession. I had never before considered that there might be more than one Hot-cha in the world, or that Hot-cha might be a name that he did not make up, or that it might have other meanings, but because I was in Omaha to get my back looked at by the very important doctor there I decided that this meant good luck for me and for Hot-cha.

One problem with riding in Hot-cha’s car is that he plays very loud rap music. And because my head lays down in the backseat it is very close to the big thumping speakers he put in himself. The first time he put these speakers in he didn’t read the directions and the back seat caught fire which ruined the speakers and the seat at which time Carlton said a very funny thing, “Ooh…Hot-cha!” When I think about Carlton saying that, with the perfect timing which is necessary for good jokes, I giggle. But Hot-cha can’t hear me over his fat beats which he spells p.h.a.t. and which stands for pimps, haters, and thugs, according to Hot-cha.

So when we pull into the parking lot there is a man leaning against the trunk

of his sports car in the spot next to the one Hot-cha chooses. In addition to

my abilities to hear, smell, and sense things I always know when someone is

trouble. I call this power Nuture-vision since I don’t think that it is genetic,

because when you grow to be as tall as I am at an early age there is always

someone looking to make trouble with you. And when Hot-cha gets out of the

car and starts arranging his pants and his necklaces the leaning man says,

“What up, Homes?” There are many ways you can say a statement like that,

and there are probably many ways you can say any word or phrase. Carlton

once told me the Inuit peoples of Canada have over 3,000 ways of saying the

word snow, for example, so that they know if they mean snow storm, or snow

cone, or snow that I just peed on. The way the leaning man said “Homes”

was clearly mean and sarcastic, which no question hurt Hot-cha’s feelings.

“Sup?” he says back, but he says it very quietly, as if he doesn’t want both

me and the leaning man to hear him.

“What’d you say, HOT-CHA?” the man says, you could tell he read that off

the license tag and used it to make more fun of Hot-cha. The man pushes

himself off the car he’s been leaning on with a snap of his spine. My back feels

so sore that I envy the ability to do something like that, but you should know

I’d never use body language to start a fight. There are times, though, when I

can to use my body language to stop a fight, so I get out of Hot-cha’s car very

slowly. I crawl, putting my right foot onto the ground and then pushing my

shoulders through the door opening so that I can reach around with my left

hand and slowly place it on the roof of the car. My hand spreads out like a

tarantula when I do that and I find that it is a good first maneuver. Then I

grab the top of the door with my right hand even more slowly pull myself

upright, which at this time shoots a terrible pain down my right leg that I

channel into a very displeased look that this man should be messing with my

very good friend Hot-cha, and I turn slightly to look down at him.

“Holy cripes,” the man says, and he jumps back around to the other side of

his car.

I slap the roof of Hot-cha’s car so that it makes a loud tingly splat that we

can all feel in the back of our necks and I say to Hot-cha: “Aren’t you ready to

eat yet? I don’t need to sit here all night with you yakking away while I feel

hungry enough to eat the bones off a bear!” Me and Hot-cha laugh a little

and then head toward the restaurant.

Hot-cha turns to the guy as we walk by him and says, “Have a good night,

Homes,” but here’s the difference: Hot-cha says it nice, like he really means for

the man to have a good night, not like he’s making fun or being mean.

I don’t like to play that card because it doesn’t always work. Sometimes a

mean guy will see how tall I am and he’ll get what Carlton calls David

Syndrome. Maybe I’m strong compared to some, but because I don’t ever

want to fight with anybody the mean guys can sometimes beat me, unless

they’re too drunk, which a lot of them are and which makes a lot of them mean

to begin with. That’s also why Hot-cha and I don’t drink, which I’m guessing

you didn’t imagine when I first told you about Hot-cha. Hot-cha’s dad died of

cirrhosis, and Hot-cha still misses him because before he got sick his dad did

things like take Hot-cha fishing for channel cats on the Platte River and throw

the ball around in the yard with him and bowling sometimes, too, when he had

the scratch.

My dad couldn’t throw the ball around with me on account of how tall we

both were and how that made it so I wasn’t very coordinated for a long time.

For a long time the doctors thought I might need to walk with crutches if I

didn’t stop growing and that I could be crippled, but that didn’t stop the

basketball coach from wanting me to play, even though I couldn’t run and

couldn’t catch the ball he said God wouldn’t have brought me to this town if it

hadn’t been to help him win a championship. So for one whole season I stood

in front of the basket and made sure no one put a ball in there. I set the

state record for blocks in a game, but there is a rule against guys my size that

says they can’t stand in the painted part under the basket for more than 3

seconds or the other team gets to take free throws, and so we lost enough

games that made our coach question God’s wisdom and he too started

drinking and giving me a hard time when I see him around town, which

thankfully isn’t very often.

Stiv and Lois’ is quiet for a Friday night and it’s no problemo for us to find the

big table by the kitchen door where Carlton is sipping on a tall beer. Stiv used

to be in a famous punk rock band and though they play muzak over the house

speakers now, the walls are all covered in pictures of Stiv mugging with other

famous punk rock stars and with people such as John Belushi, who liked punk

rock stars. We never see Stiv in the restaurant anymore, though he used to

come in and wander around the tables barking at the busboys and waitresses

and telling stories about how such-and-such punk rock star used to take

suitcases full of drugs or how such-and-such punk rock star used to pee all

over every hotel room he ever stayed in while people enjoyed their steaks. I

love the earthy smell of the steaks at Stiv and Lois’ which remind me of when

my dad worked at the Kroger and would bring home day-old steaks for the

grill which made him very happy on account of how we got to eat steaks so

cheaply.

Lois still comes to the restaurant to do some barking but she doesn’t tell

stories. She met Stiv at a show he did in Minneapolis and thought she’d really

hit the big time, but then Stiv said he couldn’t keep going with all the punk

rock. Who was he supposed to be anyway, Iggy Pop? So he took the money

from that song “I Love My Little Huffer” that everybody in the Mid-West knows

by heart and bought this steak place and a gas station on the other side of

town by the interstate. I don’t even know where they live but Hot-cha says

he does. He says he has a cousin who put a pool in their backyard and that

their house is really weird and full of stuffed monkeys.

Carlton wears fingerless gloves, no matter the weather, after something he

saw in a movie. “Though you might be tired and pushing hard, your sheer

presence and thoughts inspire others,” he says to Hot-cha as we sit down at

the table. “You might keep a lot inside,” he says, turning to me. “As a result,

sometimes you react more strongly than necessary.” Carlton also memorizes

the horoscope every morning and he knows that Hot-cha is Aquarius and I’m

Capricorn, though, he told me, I’m really a cusp and could be considered a

Sagittarius in some cultures.

Our waitress drops a couple of menus in front of us and sloshes some water

into the dimpled plastic cups before she leaves. What I like about waitresses

is that they tend not to be judgmental, probably from years of bum-looking

guys tipping big bills and the occasional guy in the top hat and spats sticking

out his empty pockets at the end of the night like the poor tax card in

Monopoly. “Yo. Did you check that out?” Hot-cha says.

“Did I check what out?” I say.

“Her arm, man. Somebody ain’t playing nice. Check it out when she comes

back.” And I do. Her arm has a dark purplish bruise on it in the outline of a

human hand. It wraps all the way around her forearm the way an expensive

piece of Egyptian jewelry might.

“What’s with your arm?” I ask, but when I look at her face I can see that

she had put a lot of makeup on to hide more bruises. Her face is pretty under

all that make-up and I can believe she turned a lot of heads in her day. Her lip

is split but healing over, which lips have to do very quickly because most

people use them so much. Some people speak over 40,000 words a day,

which would be ballpark for Hot-cha but more than twice my output. Carlton,

it depends. Some days I could see him speaking 40,000 words, like when

there’s going to be an eclipse or when he’s beat another Russian player in the

online game World of Warcraft. But mostly I’d guess he hovers around the

20,000 mark as well. Inwardly, though, I can fly through millions of words in a

day. My extra peremptory powers of perception tell me that our waitress is

inwardly verbose as well. Her eyes, for example, move around the room like

conductor’s hands while she waits for our order and I’ll bet each mental note

rings out a dozen or more words. And just so you know, in case you want to

start keeping track, you can’t count what I’m telling you here because these

are my words, not yours.

Our waitress explains, “My ex-boyfriend’s a falconer. I help train.” Carlton

leans back in his chair and throws one of his legs onto the corner of the table,

nearly spilling his beer and all our waters. He does this when he wants to

show off his knee-high deerskin boots with the fringe down the calves, though

why he wants to impress our waitress is a mystery.

“Last time I counted, falcons don’t have four fingers and a thumb,” I say,

though your guess is as good as mine why I would get involved. The older

you get the deeper your troubles, and, pretty or not, she’s much older than

me.

“Know what you want to eat?” She chews a rope of hair and then spits it

out, turning the wounded arm slowly away from our views.

“Falconry is the sport of kings,” says Carlton. “It dates back to the Assyrian

king Sargon II. He would train the falcons to snatch young goats and children

from the neighbor kings’ land.”

“Yo. My brother went to this boyscout thing at his scoutmaster’s house with

falcons and one lifted its tail and shot a load across the room like a bullet,”

Hot-cha says, slapping his hands together and then letting one hand dribble

down the other for effect.

“Little known fact: French barons used to hunt with buzzards,” Carlton adds,

pushing his glasses back onto the bridge of his nose. He’s worn the same pair

of glasses since eighth grade. We must be excellent friends to know each

other so long.

“You want me to just come back when you’re ready?” our waitress asks.

She slips her order book into her apron and covers the bruises on her arm

with her free hand.

“That will not be necessary,” Carlton says. “My comrades and I enjoy the

same victuals every Friday at this fine eatery…” And he goes on and on to

order our steaks until I’m sure she wishes her last question had been more

like a statement.

“Yo, what was up with that arm?” Hot-cha says. “Isn’t she a little o.l.d. to be getting bitch-slapped by some pigeon racer?”

“Little known fact: The Chinese are all born at age one, making them, in essence, a year older than they really are.”

“She ain’t no Chinese!” Hot-cha says. “Can you believe this guy?” heaving his thumb at Carlton.

I pull my shades on so that I can watch our waitress as Carlton tries to explain his segue rationale to Hot-cha. She is older than we are, by at least twenty years, making her roughly the age of our mothers, but she doesn’t in the least remind me of any of our mothers. My mother, for example, would never at any age have worn her blouse unbuttoned so that her brassiere showed, nor would she cock her hip sexily toward a customer who made her laugh and then chew on a loose piece of her straw colored hair while she thought about a rogue falconer back home already drinking, though he promised he’d quit, or at least wait until she got home. Anyone with the ability to see all this would describe the falconer as dangerous. Wanting to invite your sister to come over, for example, can not be a good reason for him to get that upset, and it certainly makes no sense that this falconer, much, much bigger than she, would grab her arm so roughly, the pinch and the pain of which would literally buckle her knees until she hung from his grip, the tattoo of a dragon roiled on the shaking sea of his forearm. Who can tell what someone like that would be capable of? Perhaps something no one could ever forgive; something unforgiveable.

As we eat our meals Hot-cha learns that her name is Mary-Anne, to which of course Carlton provides: “In her signature song, ‘Proud Mary,’ Tina Turner actually changed the word ‘pain’ in the lines ‘Cleaned a lot of plates in Memphis, pumped a lot of pain down in New Orleans’ from John Fogerty’s original lyrics to ‘tane’ and in octane, meaning fuel.”

“And?!?” Hot-cha replied. “Yo, Proud Mary, give my man here another beer and put it on my tab. Maybe then he can tell us how Anne used to be what Edith Wharton called her guitar or some hoo-hah.” And so we called her Proud Mary, which she seemed to like.

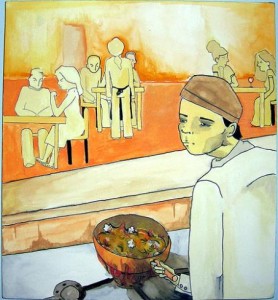

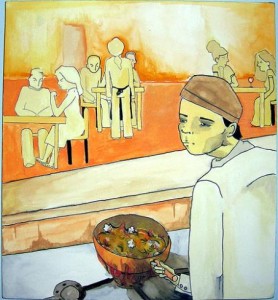

For several Fridays in a row, though, Proud Mary would visit our table with new bruises on her arms, all of which owed to the work of her falconer and not, as she insisted, his falcons. Seeing these bruises sometimes gave me such a deep and low, sad and tired feeling that I wanted to return to the thermic core. Then she showed up with a mark around her neck.

“You letting his little birdies sit around your throat now, Proud Mary?” Hot-cha asks, when the more obvious questions no one would ask.

“Well, I’m through with falcons, if that’s what you’re wondering,” she said. “They’re loud, they smell bad, and they don’t know how to treat a girl. So if any of you thinks of a good place where an old chick like me can park her behind for under $300 a month you’ll let me know. Now, does the steak crew feel like living on the wild side, or should I just turn in last week’s carbon to the cook?”

After our dinner Carlton finishes the last of his beer and a long story about how the FBI has secretly reopened Project Blue Book, their covert study of ufology that has archived and suppressed hundreds of witness accounts of ufos in all areas of the country including three in our own. “No butter-bunk, Homes,” Hot-cha said. “My uncle’s riding his tractor when he was just a kid on the farm and this big disc comes out of nowhere, hovers over him until the engine dies, and then blows out of there at a millions miles an hour. And when my uncle got off the tractor his dog came running up speaking fluent Portuguese for about twenty minutes, but then he couldn’t talk no more, in any language. Wouldn’t even bark, unless he saw a squirrel. Yo. You homies ready to clip?”

“You two go on,” I say. “I’m going to walk home.”

“Walk home? W.T.F., man? You can’t hardly walk across the room without your back sounding like Chinese New Year!” Hot-cha says.

Carlton pushes his glasses up on his nose and then looks around at the emptying restaurant until he figures things out. “Let’s go, Hot-cha. You can give me a ride home,” he says, shaking his head slowly at me as if he does not approve of what I am about to do.

“Later Homes,” Hot-cha says. “But don’t go calling me just cause you’re only down at the next block and can’t make it no farther.”

“Your little friends leaving you alone tonight?” Proud Mary says as she scoops up the remaining plates and glasses from the table. The bruise on her neck troubles me deeply. All bruises trouble me deeply.

“Proud Mary,” I say. “Can you give me a ride home this evening? I might have a place that can help you out.”

She looks plainly stunned, but really I know that she is frightened by me, which I wish wasn’t the case. And perhaps you’re thinking what woman in her right mind would let a giant into her car and then drive him home, alone? But Proud Mary knows better than any of you. She could see that though I am giant, I am a decent man with only the most decent of intentions. To say nothing of my safety, which you’ve probably overlooked. Some might say that she’s trouble, and that trouble brings trouble. I sit at my table for another half an hour until the last of the customers heads out of the bar, sipping ice waters that Proud Mary keeps coming with which, I can tell, means she’s getting nervier.

She tries diffusing the awkward silences between us on the walk through the parking lot with too much chit about how I probably won’t fit into her tiny car, but little does Proud Mary know her car is much larger than Hot-cha’s voluble machine. Her car also makes it seem as though a family of hobos live in it. A great unpiling of piles takes place before we find the seat and before the seat will recline. “I had to throw a lot of my stuff in the back here as I’ve flown the coop. Truth be told I’m not a neatnik, but I’m not this much of a slob. Usually. You’ll have to guess on the in-between.” I direct her to my home, which is close enough that there is kindly no need for further conversing.

Getting out, though, never ceases to present a challenge, but Proud Mary runs around to the passenger side to assist me as best she can. At this point I see the top of her head and the dark and white roots where her color recently grew out. I also like the smell of her, like steaks. So maybe this is not the smell of her that I’m liking, but the smell from the entrepreneurial imagination of Stiv and Lois, which would still fall into my extra sensory

peremptory purview to smell things like one person’s imagination drifted onto somebody else.

“This is your place? All this?” Proud Mary says as I fumble my keys.

“My father, he died a while back, and my mother moved to be near my sisters in Kansas City. So they left me the house.”

“I’m sorry about your father,” Proud Mary says, but she’s already inside by the coat rack. Proud Mary carries the steak smell all over the house. “How many rooms are there?”

“Several,” I say. “I don’t go upstairs, much. Those rooms up there don’t have such high ceilings. They were always the women’s rooms, and you’re welcome to either of the two on the south end, if you think you might want them.”

“These are beautiful ceilings,” she says, meaning the crown molding which is something I’ve always thought beautiful too, but didn’t realize until she pointed it out. “What’s in here?” she says, reaching to open the door to the dining room.

“Wait!” I say, and before I can control it my big hand swings down hard-like and snatches her wrist from the handle. I raise her hand up until I’m also pulling her off her feet and then let go suddenly, back in my own mind again.

“Sorry. I’m sorry,” I say. “I should just show you myself.”

“You need to be careful,” she says, rubbing her wrist. “I bruise easily, you know.”

I push open the door and duck my way past her into the dining room. I leave the overhead lights off, which I usually do anyway, so that she can take in the full effect. I even make a little flourish with my hand as she enters the room. “The thermic core.”

“What are these then? Snakes?” she says. I’d expected more oohing and ahhing.

“You don’t like snakes?” I say.

“Not really,” she says. “I don’t mean I don’t not like them, I’m just wondering what it is about men and their pets. Men with dangerous pets usually want to make a pet out of you, I’d say. Wouldn’t you agree that statement to be a true fact?”

“But they’re beautiful things, these snakes. Look at this one, for instance,” I say, taking my favorite right off his hot rock and letting him slip between my fingers. “He’s an albino ribbon snake – sweet as you please. Or, over here,” I take out another little friend in my other hand. “I’ve got a long nosed snake. He’s equally sweet, but very difficult to get to eat…”

“You feed them mice and rats and the like?”

“Well, yes. That’s their natural diet in the world. Did you know that the symbol for alchemy is the snake, the science of turning-to-gold? Did you know that snakes also represent medicine and healing? And I’ll bet you were not at all aware that the snake was the symbol for Jesus the Redeemer at one time?” This last fact usually floors any denomination.

“So do you breed your own rats and mice or do you have some enormous credit down at the Pet-Co?”

“I only have to feed them once a month or so, except for some of the smaller ones. I just go get their food then,” I say.

“That’s good, because I can’t tolerate cages of rats on death row.” The various glows from the tanks all light up Proud Mary from twenty different angles, as if she’s suddenly a star caught in the frozen paparazzi bulb crush. This glow does her well by brightening her skin and eyes and evening out the color of her hair. “Hot in here, isn’t it though?”

“It helps my back,” I say. “To keep warm. Most times I fall asleep in here on the floor.”

“Don’t you have a bed?” she says with great incredulity.

“They don’t make beds for people my size. Not that I can afford, any how.”

“Let me go look upstairs,” she says suddenly. “And then maybe we can work something out. I’d planned to go to my sister’s tonight, but I’m thinking that would just bring more trouble down on her, and she’s got a new baby and a bunch of slobbery dogs that won’t let me get no rest anyway.” When she leaves the thermic core I crumple onto the warm floor to let my spine unfurl, only the thin sound of little, rustling bodies and the distantly familiar

echo of footsteps upstairs keep me from falling under a deep sleep.

“This is great,” she says, sticking her head cautiously into the thermic core from the hall. “Do you mind if I bring some stuff in and get situated up there? I don’t have much, and if this doesn’t work out I can take off in the morning. Hello? Are you okay?”

“I have a bad back and an enlarged heart,” I say. “This helps.”

“You just wait until I’ve had a shower,” she says, and I mourn the loss of the warming scent of steaks on her. “I know a trick or two about backs.”

“Uh-huh,” I say, and its too late, too familiar, the sound of a woman’s voice scurrying around upstairs, the groan of the pipes over me as the shower commences, and before I know it I’m back these years, laid out on the floor, while my mother is loading the car to leave for Kansas City. What I didn’t tell Proud Mary, and why should I, is that my mother left before my father died. As his heart trouble grew worse so did his moods; he had this anger deep inside of him, from years of being the town freak, no doubt, from all those stares and all that stooping over to walk through the doors every other person in town walked through with ease. I suspect now that some of his heart medications, which I’ve been prescribed but refuse to take, led to his dementia because what else could drive a man to lock himself in this very dining room for a week or spray paint ‘HARLOT’ and worse onto the upstairs doors? It took several coats of very dark primer and a lot of embarrassing silence for Hot-cha and Carlton and me to cover the sprayed on words.

My father’s moods roiled over and could not be contained, even though he’d been loved by my mother, by my sisters, and by me. “I can’t let him keep doing this to us,” my mother finally said, meaning the tearing down. She kneeled down in the thermic core (which was cold then and without snakes) beside me while I pretended to be asleep, immune to everything. “Please. Please don’t ignore me. I want you to come with me. He’ll turn on you too, and as big as you are I know you’re sweet inside, and you won’t be able to keep him off of you when he gets into a rage. He was a good man, Son, he was a good man and I’ll always love that. But that’s not in him any more. You can come with me, come be with your mother. Please.” When the deep blue days come now I often try to imagine different ways my hand could’ve flown up accidentally, fantasies about still undiagnosed seizures maybe, or some way my mother might’ve slipped, leaning down to plead with me, so that, really, it was the hard floor that hit her face like that and not me. At worst I comfort myself knowing that I have matured enough now to achieve complete self control, even if no one is around to appreciate my new improved self. If I hadn’t achieved this mastery do you really think I’d have these extra sensory powers?

“Whew! It feels so great to be free from the day!” she says, standing next to me now. Her feet are naked, her toes painted bright red, and she’s wearing a pink robe with pink feathered fringe that keeps falling off like snow flakes behind her. The smell of soap has eclipsed the warm smell of steak, which I don’t like as much. “Roll over,” she says. “Onto your gut.” Which I do. She climbs onto my back and I see the feathery robe come fluttering down to the ground a couple of feet from my face. She kneeds my back with her painted toes and it feels both good and bad. “Not too high,” I say. “I have an enlarged heart.”

“Well, it’ll take me a good fifteen paces to get to where your heart is from down here, but you let me know when I get too close.”

“I’m going to die young,” I say. “Giants die young. My father only got into his mid-forties before his heart quit.”

“Make the most of your time, then,” she says, squeezing the skin at the base of my spine and pulling it upwards with her toes. When she hits a sweet spot I feel like I’m flying, the pain holding me to the ground dissipates until I’m soaring.

“I wasted the last ten of mine with that lout, so don’t think we’re not running neck and neck.” I hear her breathing and the gwish, gwish, gwish, of her steps under the hum of the hundred lights and singing rocks and the snakes rolling back and forth across the glass like windshield wipers just after a rain stops.

“Do you think you’ll be bringing any, uh … bad choices along with you?” No reply comes. “I mean, you don’t think fouling up is like a permanent habit for a person, do you?”

There’s no reply, just the gwish, gwish, gwish of her feet on my back and the hum and sway.

“Lower,” I plead. “Lower. It feels like flying straight off the ground when you’re in just the right spot.” And she steps into the perfect spot, further away from the danger with my heart. You only wish you had such relief near the end.

Darren de Frain gives sincere thanks to Editor Joel Deutsch for his enormous patience with his story. DeFrain received his degrees from Utah, Kansas State, Texas State and Western Michigan. He is author of the cult novel, The Salt Palace, and numerous stories, essays, and poems. He currently lives in Wichita, Kansas with his wife, author Melinda DeFrain, and their two daughters. He directs the MFA Program at Wichita State University.