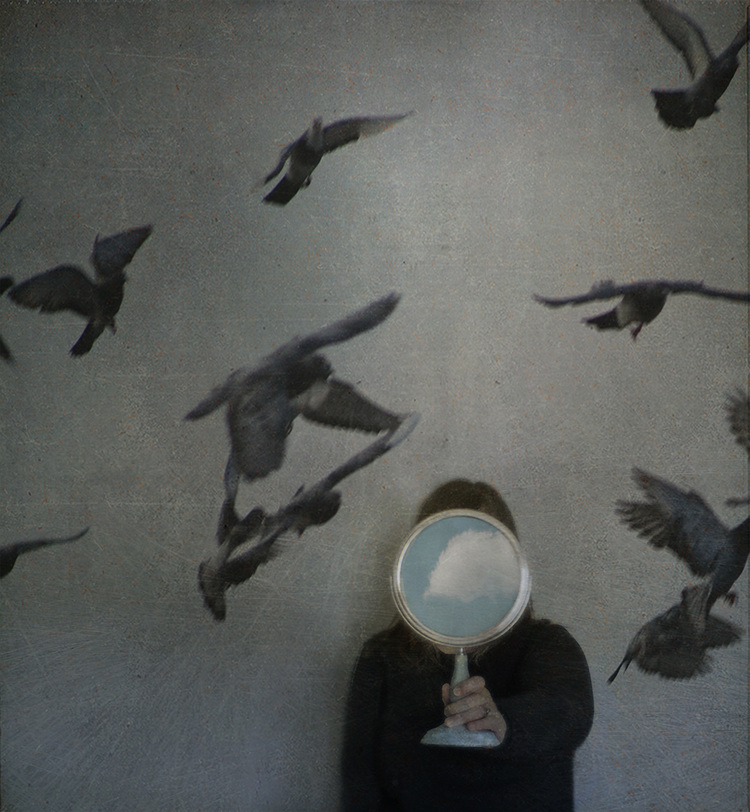

“Foggy Bridge” by Penelope Breen

Mark was six- or maybe seven-years-old when he started climbing on the fences. He walked along the top railing with his arms spread out and looked down at his feet, smiling. I can picture just how his smile was and his shoes were muddy from where he’d been running in the field.

“You’ll fall,” we told him, his father Clive and I. “Watch out.”

“Watch this, Mama,” he said, hopping from one foot to the other on top of the fence, like the ground was a hot and burning thing he didn’t want to touch.

In the distance, a chainsaw whined and buzzed and close by squirrels skittered on a branch and acorns fell. The wooden fence creaked under the weight of him, but he kept going. And we didn’t know how soon we would start losing him.

The older Mark got, the more he was two different people. Some days he wanted everything and talked all the time and needed to be moving every minute. And other days he was emptied out and didn’t see the point in anything. Still, a losing like that doesn’t come all at once. It comes at you in little pieces. You’re asking don’t you want to get up and go outside and you’re saying settle down, just settle down. The whole time looking for the middle, settling-in place he needed.

The last time I talked to him he was twenty-three and about to be married. I went to see him out at the lumberyard where he was working because I knew something was wrong, but he wouldn’t tell me what it was. He was moving slow that morning like he was underwater.

Later that afternoon, the phone rang at the house and I took the call and got to the bridge as fast as I could. A girl stood there, crying and screaming and biting her hand. She wasn’t his fiancé. I’d never laid eyes on her before and I didn’t know what kind of trouble Mark was in. He wasn’t around anywhere, not that I could see. I looked out over the bridge and past the trees and the rocks. Either the girl stopped her crying or I stopped hearing it because everything turned quiet when I saw him. Mark was way down at the bottom of the gorge, blurry and far away and not moving.

When he was part of the air, I wasn’t there to see him. By the time I showed up, he had become part of the ground with the dirt wrapped around his shoulders like a coat and I looked away without seeing the rest. But I could picture what he must have looked like before, when he was part of the air, his arms spread out and him not wanting anything except to fly, the ground a hot and burning thing he didn’t want to touch.

Heather Adams, winner of the 2016 James Still Fiction Prize, has published short fiction in The Thomas Wolfe Review, Clapboard House, Deep South Magazine, Broad River Review, and elsewhere. This story is based on her first novel, Maranatha Road, which is forthcoming this fall from West Virginia University Press.

This flash fiction first appeared in Pembroke Magazine (Vol. 47, 2015)

Read more about the inspiration for Heather’s story here.