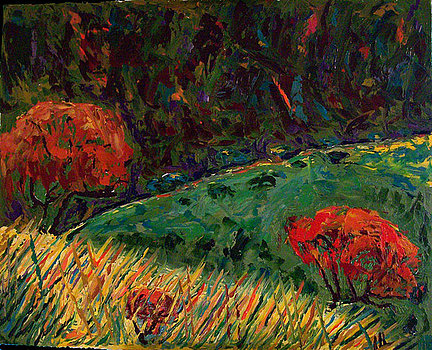

“South African Hills” by Allen Forrest, oil on canvas

Fifteen years, his unruly, upstairs neighbor likes to remind him in those empty, uncertain hours of night, is twenty percent of the average American male’s lifespan! That’ll throw a wheel out of balance!

Of course, he knows this, can in fact still hear his lawyer arguing on his behalf, that time served is time he cannot replace. Taken from him. Gone.

Fifteen years! his neighbor points out, as if he’s forgotten, as if he hasn’t thought about it nearly every minute of every one of the ninety-nine days he’s been on the outside. Which is why he keeps the radio on, morning, noon, and night. Silence is a rabble-rouser.

Although he was exonerated, his name cleared, he didn’t get everything back. How could he? When he thinks about it like this, late at night, lying there in that fragmented apartment, trying to remember faces, names, numbers, and what the world looked like before, before, even the quarter-million-dollar settlement his lawyer negotiated for him seems inadequate, inconsequential. Unless…he can’t be sure.

He heard disbelief’s voice for so long that eventually it moved in with him and became his cellmate. Then one night his memory slipped through the bars and escaped, and suddenly he couldn’t recall a time when he hadn’t doubted, when he hadn’t seen himself through the eyes of others. After all, if he’d needed any evidence, there he was, wearing orange shame, eating for sustenance rather than pleasure, with no use for a calendar. And yet he was innocent. That’s what he always maintained. Innocent. That’s what his lawyer had argued. Innocent.

Technicality: that’s what everyone else said. Even after DNA evidence helped overturn his conviction. Even after the newspaper dedicated three column inches to setting the record straight. Everyone said it was just a technicality. Just a glitch in the system. A minor detail had set him free.

His lawyer said to ignore them, said to look forward, not back, said to get on with his life, that he’s only thirty-five, that—if one could believe statistics, research—he’d probably live another thirty-five.

It’s going on four months now and though disbelief packed up and went away he can still hear self-doubt stumbling around upstairs in the cruel, wicked hours of night, rattling him with its shackled footfalls, hurling antagonistic slurs—fifteen years!—as if it has nothing better to do than stay behind and torment him.

Other than groceries—just the basics; a learned behavior which has become habit; but then again his idea of eating well has always been getting enough to eat, hasn’t it?—and batteries for the radio, which he buys in bulk, the only thing he’s sprung for so far is a pair of reading glasses, faux tortoiseshell cheaters that multiply like rumors and which make him feel like an historian as he scans the residential listings at his local library, reveling in the room’s wide-open space and the vague camaraderie of the other visitors as he scrolls through screens, scanning, the hairs on back of his neck bristling occasionally, his head jerking and twisting whenever someone approaches from behind, then the breathing techniques, deep breaths, and the counting and holding and waiting as he centers himself in the winter of his fuzzy, if familiar, discontent. And all the while he never stops searching for names that might help him fill that fifteen-year void.

He tells himself that perhaps he can connect with someone he used to know, a friend or former co-worker from the car lot, which is now just a tire shop. Or maybe he has some family left, someone out there somewhere who can remind him who or what he used to be, who can substantiate that what he believes—what he wants to believe—is true, that his freedom is the product of something innate, something more than the minor technicality his upstairs neighbor insists. He has money now and he tells himself that he’d spend all of it to prove he is who he always said he was. And if he can’t do this, he thinks, what’s the point of going on? What use is money, even a quarter million, to a man who can’t look at himself in the mirror, tell himself he’s innocent, and really believe it?

John Gifford (@johnagifford) is the author of the story collections, Wish You Were Here (Big Table Publishing, 2016) and Freeze Warning, which was named a finalist for the 2015 Press 53 Short Fiction Award. His writing has appeared in Harpur Palate, december, Southwest Review, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Oklahoma.