Joan Wilking: Both my SOS piece (At Risk) and yours (Grip) were inspired (or triggered) by five word prompts posted in an online flash fiction workshop we’ve participated in for years. What has the use of such prompts and membership in the workshop meant to your writing?

Kathy Fish: Great question, Joan. I saw someone recently decrying the use of prompts in writing, saying they resulted in inauthentic writing. Nonsense. To me, writing prompts such as the ones you and I get in our flash workshop, are simply kindling. It’s up to each writer to set the sticks and twigs aflame. And what we do to start the fire comes wholly from within us and is therefore completely authentic.

Kathy Fish: Great question, Joan. I saw someone recently decrying the use of prompts in writing, saying they resulted in inauthentic writing. Nonsense. To me, writing prompts such as the ones you and I get in our flash workshop, are simply kindling. It’s up to each writer to set the sticks and twigs aflame. And what we do to start the fire comes wholly from within us and is therefore completely authentic.

I’m often struck by how, given the same five words to work with, we in the workshop create such utterly different and unique stories. The prompt words just get things going. I’m so grateful for Kim Chinquee and you and everyone in our Hot Pants workshop!

You all have meant everything to my writing life. I doubt I would still be at it today without you. There’s such huge value to having a longstanding group with whom to work. We all know each other well, know our quirks, and strengths. We’ve taught ourselves over the years how to relate to each other in a way that brings out the best in our work.

I’m interested in how it is for you, Joan. I know you have recently been using the workshop and prompt words to create a memoir. Can you talk a little about your process in putting that together?

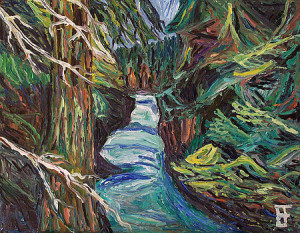

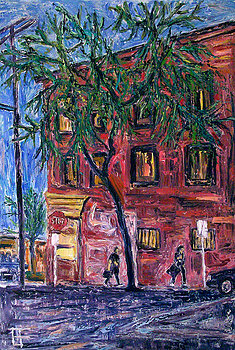

JW: I love the kindling analogy. Because I was a graphic designer long before I ever tried to write, my work pretty much always begins with an image. The prompt words, more often than not, force me to think beyond the imagery. They light a fire, as you said, that quite often changes how the piece eventually evolves, sometimes by adding a twist that enhances the story, sometimes by enriching or challenging the language.

As for my process, when I’m writing fiction I tend to take familiar situations and “awfulize” them. Years ago I read a Joyce Carol Oates novel and thought to myself, ‘She must have the best time taking her characters and putting them through more misery and heartbreak than any non-fictional character could survive and then manipulating them to enable them to come out the other side.’ Manipulation of character is a good term for how I see fiction.

Memoir is something else. For me it’s about mining the feelings attached to remembrance without straying from the truth. On my 70th birthday, this May, I started writing seventy pieces, seventy words each, for seventy days, alternating the past and present. I used the Hot Pants prompts in many of them. That was a very personal journey and I don’t think I could have completed it without the sense of safety the Hot Pants workshop provides.

That’s a true tribute to Kim who has been so passionate about keeping it going, and of course to everyone else who shares there.

You are known as a flash fiction aficionado. I often end up using my flash as a steppingstone to my longer fictions. I’m wondering, after the work you share on Hot Pants has been critiqued, how much of it remains flash and how much, if any, becomes part of longer works, which all begs the question, what role does flash fiction play in the ongoing panorama of literary history?

KF: Wow, I really love the notion of taking a familiar situation and “awful-izing” it! Yes, putting one’s characters through hell. I’ve heard variations on this idea. It really does make for potent fiction and is a great way to approach flash fiction.

You know, my flash pieces from Hot Pants very rarely turn into longer works. They almost never go beyond flash length. I do remember one time posting a really odd paragraph in there and one of our group, I think it was Gail Siegel, responded with such unexpected enthusiasm, I just wrote and wrote and wrote and ended up with 3000 words, which to me is a tome, ha. It ended up being one of my favorite (of my own) stories. And there again is the huge value of that group.

But no, usually my stories remain flash. I honestly don’t know what role flash fiction will ultimately play in the literary canon. Those of us who write it are so passionate about it! My sense is that is ought to remain a fluid form, that it’s too early to lock it down. I get so excited when I see people doing different things with it. I say as long as it’s fewer than 1000 words, it’s flash. Well, maybe a 1000 word grocery list doesn’t qualify, but you know what I mean. I rather like the idea of flash being the rebellious teenager of the literary world.

I wonder if visual artists, actors, directors, musicians approach writing differently. It has to inform the work. As you said, you nearly always begin with an image and then you move beyond image to story. Lately, I’ve been trying to take a very cinematic approach to writing, though I have no background in film. Do you do this as well? Would you like to see any of your work committed to film or stage?

JW: A couple of years ago I was in Mexico with a bunch of writers and J. Ryan Stradal, author of the new best seller, Kitchens of the Midwest, read a story that was a series of grocery lists, which was hilarious. Each list was a little flash story.

I used to participate in a group called Writers & Actors INK. We met once a month is a black box theater. Writers brought short scripts or stories and actors came to read from them. It was amazing how differently some of my stories played out in front of an audience. What I thought was funny actually had people in tears and vice versa; people saw humor in what I’d written as tragedy. I’d love to see my work on stage or screen where the visuals have parity with the words. I hadn’t thought of my work as cinematic, at least not consciously. You may have just changed the way I perceive it.

We haven’t talked about our stories in r.kv.r.y. yet. Can you speak to the origins of your story?

KF: Oh yes. Can you imagine a series of short films or plays based on Hot Pants stories? That would be so great. I can see how all of us would write to that idea, you know? Not changing our flashes to screenplays or stage plays, but keeping in mind that they may be seen.

My story, “Grip,” is only slightly fictionalized. In March, my brother died of multiple sclerosis. I’d gone home to Iowa when he was in hospice. It was one of the most profound experiences of my entire life. I came back feeling incredibly sad, of course, but also just…dazed. And for a time, every single thing I wrote stemmed from watching my brother die, watching my family watch him die.

As you know, we take turns in Hot Pants providing the prompt words. When it was my turn, I gave five words in honor of my brother. I don’t remember exactly what they were, but I know I used them in the story. The title, “Grip” came from one of those beautiful moments, one of those gifts you get in the midst of tragedy, when—weak and depleted as he was—he squeezed my younger brother’s hand very tight (for story purposes I made it my own hand). It spoke to so many things, that moment, and I knew I’d eventually write about it. I’m glad I did.

Now, please tell me a little about your story, “At Risk,” Joan. I love the opening sentence: “I think a lot about ghosts these days.”

JW: I think many writers, including you and me, use writing as a way to process pain.

Other than ad copy, I never wrote until I was well into my fifties, never thought of myself as a writer. I never had the undeniable passion to write that some writers do. As a result, when I started, I felt like a freshman. Now I read the work of young and younger writers, and workshop with them, and feel like I fit in better with them than with many of my age-wise peers. That has led me to do a lot of thinking about how we marginalize groups of people according to age. Google me and my age is apparent. I wonder how that influences how other writers, agents, publishers and editors view someone like me.

“At Risk” is based on observations that keep piling up as one enters old age. So many losses offset by the smell of lilacs and fog on the Bay, and the young, always the young, around to envy and be a reminder, when they look at you a certain way, that the end is a hell of a lot closer now than the beginning.

And one last question, if there was only one more thing you could accomplish in your writing career, what would it be?

KF: Oh man, I could NOT relate more to what you’ve said here. I, too, came late to writing. I, too, feel I have more in common with younger writers. And I also wonder at the marginalization of “older” writers and artists. Can only young people “emerge” for instance?

And I relate, keenly, to your story, to those feelings. Ah, but we keep those feelings at bay by just living and creating all we can. I guess. Ha.

Wow, your question is a good one! I can tell you, that I used to think in terms of awards and honors and recognition. Now, for some reason, I find myself pining for those things quite a bit less. I think it’s realizing that the “good stuff” is in the writing itself. And what we ultimately manage to leave behind. I’ve recently discovered a love of teaching. I think if some new writer I’d had the pleasure of teaching or inspiring went on to do great things that would be a wonderful accomplishment. But hey, if I could get TWO more accomplishments, a short story in BASS would be thrilling!

I’ll volley your question back to you, Joan. One more accomplishment. What would you pick?

JW: I’m greedy. Publication of one of my as yet unpublished novels, which will land on the New York Times bestseller list, be optioned for film and made into a major motion picture that grosses a huge amount of money. Short of that, just a good chunk of time left to keep on writing.

KF: Okay, I want that for you so you can invite me for an afternoon of wine and sunshine on your yacht with all your fancy friends. You’d do that, right?

JW: Absolutely!